Soviet Modernism is an extraordinary and imaginative genre of architecture. I’m fascinated by it and even Kirsty is often astonished by some of the examples I drag her off to see! But I suspect that not everyone knows what Soviet Modernism implies so let me first explain what it is and how it came into being.

What is Soviet modernism?

As the name would suggest, Soviet modernism, sometimes shortened to sovmod by other authors, is a modern style of architecture that was prominent throughout the Soviet Union between 1955 and 1991.

The above dates are significant. Prior to 1955, the primary style across Russia and the Soviet republics was Stalinist architecture (*). Also known as Socialist Classicism or Stalinist Empire style, this ambitious, lavish and often pompous genre of architecture lasted from 1933 until 1955 and was so-called because it evolved during the period of, and was influenced by, the Soviet dictator, Joseph Stalin.

(*) Stalinist architecture was preceded by constructivism, the first of the three major architectural styles in the USSR which thrived in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Stalin died in March 1953 and he was succeeded by Nikita Khrushchev. Khrushchev would famously go on to denounce Stalin and the cult of his personality in an incredibly risky keynote speech he gave to the twentieth congress of the Communist Party in February 1956. But, prior to this, in December 1954, he addressed the annual conference of the All-Union Builders and essentially put a halt to the continuing creation of architecture in Stalinist style.

Stalinist architecture was more about form rather than function. Closely connected with socialist realism, the officially sanctioned art form of the USSR, it showcased the might of the Soviet Union, and Khrushchev and his associates wanted to change this. They desired a new style of architecture, one that would be both contemporary and functional.

Cost was also a factor. Structures designed in Stalinist Empire style were expensive and, in one of his speeches in the mid-1950s, Khrushchev lambasted the buildings of the era as being a criminal waste of money. He pointed out that the economic growth of the USSR was an essential priority and, going forward, new construction needed to be of better quality but at a reduced cost (*).

(*) The corner-cutting and the poor quality of the materials used back then are among the reasons why so many examples of Soviet modern architecture are in such bad shape today.

Initially, those same architects who had, only a few years earlier, been designing neoclassical structures on a generous budget during Stalin’s regime, struggled with the new concept. But, in time and with access to examples of modern and innovative architecture in the West, they took to the task with zeal, and Soviet modernism was born (*).

(*) The term Soviet modernism and the period it defines wasn’t coined until 2010. According to one source (written in Russian), it was attributed to a French photographer, Frederic Shubin, who spend time in the early 2000s travelling around the former Soviet Union photographing such buildings.

Flourishing as an architectural style for just under four decades thereafter, it was the collapse of the USSR in late 1991 that bought the eventual demise of Soviet modernism. During this time, however, countless structures with all manner of uses (circuses, airports, wedding palaces, hotels, universities, you name it) were built throughout every corner of the Union. And, as is apparent from the diverse examples in this post, even though the architects of the period worked under the control of a totalitarian leadership and were almost always hindered by local bureaucracy and tight regulations, somehow they still found room for creative freedom and experimentation.

Our hunt for Soviet modernism

Searching for Soviet modern architecture is often frustrating. For starters, it’s not a style that is that popular and as a result, the information out there on the Internet etc. is fairly limited. Our distinct lack of Russian, still a common language that is widely spoken in all of the countries that once made up the USSR, also doesn’t help matters. Often or not, once we’ve identified a building that we want to see, pinpointing its exact whereabouts is hard because, although asking locals for directions once we’ve established we are in the right vicinity is simple enough (we show a photo from our phone!), understanding the reply is invariably not. We can spend ages in a small area wandering around looking for a structure and not understand why we can’t find it.

And this leads me on to another issue that we frequently encounter. We often have no indication of how old the information is that we have garnered about a specific building from this era and we discovered at an early stage in our interest in the subject that a reasonably high percentage of these structures have either been abandoned, remodelled or demolished altogether by the time we’ve got around to visiting them. It’s frustrating, to put it mildly. At least if a building has been abandoned, we can still see its facade but if it has been redesigned then, from our experience, it is often beyond recognition and doesn’t resemble the original structure anymore. A location that has been demolished is naturally the biggest disappointment for us and a huge waste of our time.

Naryn Restaurant in Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan) was abandoned when we took this photo in 2016 and was then subsequently demolished in 2017

There is a plausible explanation as to why many of these buildings are in such a vulnerable situation. Besides skimping and tight budgets at the time of construction, which has led to many of the buildings from the period not weathering at all well, there is another factor to consider. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, the new governments in the majority of the fifteen countries that once comprised the USSR have, wherever practical, gone to lengths to rid themselves of these reminders of their Soviet past either by knocking them down and replacing them or by revamping and modernising them.

It is also worth considering the notion that, for many, these buildings aren’t very appealing. Similar to brutalism, which I once saw described as being like Marmite (you either love it or hate it but there’s no in-between), Soviet modernism does get a bad wrap and is often described as ugly and unsightly. Put in architectural terms, harsh concrete-overkill superstructures are not everyone’s cup of tea and the inclination in many of these countries, both within the public and the private sector, to spend money on maintaining them simply isn’t there.

Click here to see what this former balneological resort (now an aqua park) in Druskininkai (Lithuania) use to look like before it was remodelled

We obviously do like the style and from a personal perspective, all of the above does make the task in hand somewhat of a challenge at times.

It has also instilled us with some sense of urgency. Many of these Soviet vestiges still standing seem to be perpetually on death row and awaiting their fate of either abandonment, re-design or demolition. Having dedicated a large chunk of our time in the region over the past three to four years searching for examples of Soviet modernism, we’ve not done too badly but, if we want to see as many as possible before it is maybe too late then we’ve got to get a bit of a jog on.

Another factor that hinders our quest to see as much Soviet modern architecture as possible is that a number of these buildings were originally constructed to be used as government departments. Most of them have retained their original design and are therefore the most interesting ones to see but, they’ve also kept their original function and sensitivity around government-related buildings is still very much a thing in the former Soviet republics (*).

(*) I guess it is in most countries, but we aren’t so interested in photographing their government structures!

This does make photographing them tricky at times, in particular with a large and rather noticeable DSLR camera and, on several occasions, we’ve experienced difficulties getting close to and taking pictures of a place we’ve got on our list. We’ve even been shooed away by over-zealous security guards. I suspect if we spoke Russian and could explain ourselves we wouldn’t get such a hostile reaction but we don’t and a few times we’ve hurried away from the scene of the crime to the cries of words I doubt very much would appear in our Russian-to-English phrasebook!

Only once have we encountered an employee sympathetic to our predilection for Soviet-era architecture and that was at the Palace of Pioneers in the Ukrainian city of Dnipro.

We don’t often get to look around the interior of many of the buildings we search for but nobody paid us any attention at the Belarusian Sanatorium in Jūrmala (Latvia)

You might be wondering, by this point, why we don’t get ourselves another interest, but there is a bit of silver lining to this rather ominous cloud in so much that, and again similar to brutalism, there is an ever-growing appreciation for Soviet modernism these days. This, in turn, has led to petitions and whatnot that have ultimately saved a handful of these structures from getting the chop or, at the very least, a last-minute reprieve.

Arguably, social media has played a role in increasing the awareness of modern architecture in the former Soviet Union. There are a handful of Facebook groups, for example (including this one), where people with a similar appreciation share information and photographs on the subject.

Instagram is another useful social networking media and the one we predominately use to showcase examples of Soviet modernism (and other related architecture, monuments and memorials etc. from the era) that we have photographically captured over time.

Our account @ArchitectonicTravels has grown significantly over the past year or so with a community that has a genuine interest in what we are posting. It also works the other way and we find plenty of inspiration for future visits to the region from individuals and hashtags that we follow on Instagram. Instagram can be a terrible platform for follow-for-follow and like-for-like account growth practices but this doesn’t seem to happen when the subject matter is niche.

We haven’t been everywhere in the former USSR. Far from it in fact, with the Motherland itself, Russia, comprising the biggest missing piece in our Soviet jigsaw. We have spent quite a bit of time in neighbouring Ukraine however, plus we have searched out examples of modern Soviet architecture in eleven countries and three disputed breakaway territories that all once belonged to the world’s largest country.

Choosing twenty-five examples of Soviet Modernism to accompany the words in this article was difficult and took just as long as writing the piece itself. In the end, I gave up trying to balance the examples across all of the former Soviet republics we have visited and instead just picked the ones that I personally think are outstanding examples of the genre. If you want to see more then head over to the Architectonic section of our site and/or check out our Instagram feed on the subject.

Some of what we think are the best examples of Soviet modernism in the former USSR

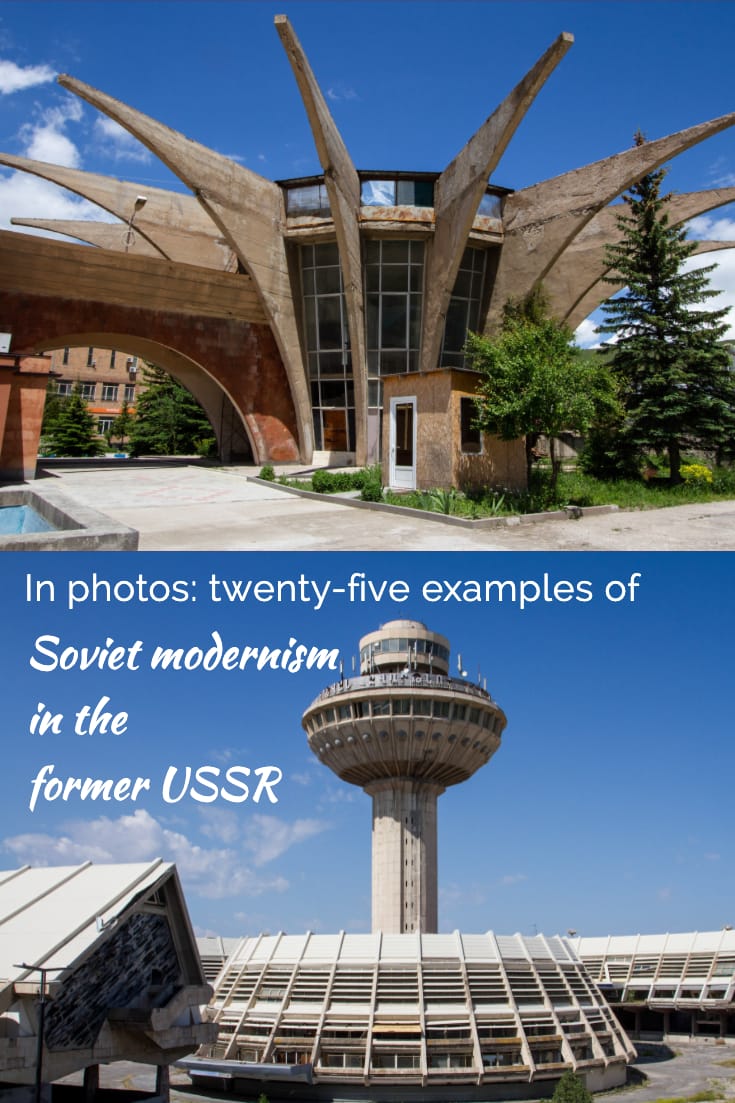

Former Control Tower Zvartnots International Airport

Yerevan, Armenia

Completed 1980

Architects Spartak Khachikyan, Zhorzh Shekhlyan, Artur Tarkhanyan and Levon Cherkezyan

Philharmonia (Kyrgyz National Philharmonic named after Toktogul Satylganov)

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Completed 1980

Architect A. Pechonkin

October Cinema

Minsk, Belarus

Completed 1975

Architect Valentin Malyshev

Sana Sanatorium

Gagra, Abkhazia

Year built not known

Architect not known

Khmel’nitsky Regional Literary-Memorial Museum of N. Ostrovskii

Shepetivka, Ukraine

Constructed 1975-1979

Architects M. O. Gusev and V. M. Suslov

Romanita Collective Housing Tower

Chisinau, Moldova

Completed 1986

Architect O. Vronsky

Canteen of the Writer’s Resort (Guesthouse of the Armenian Writers’ Union)

Sevan, Armenia

Completed 1969

Architects Gevorg Kochar and Mikael Mazmanyan

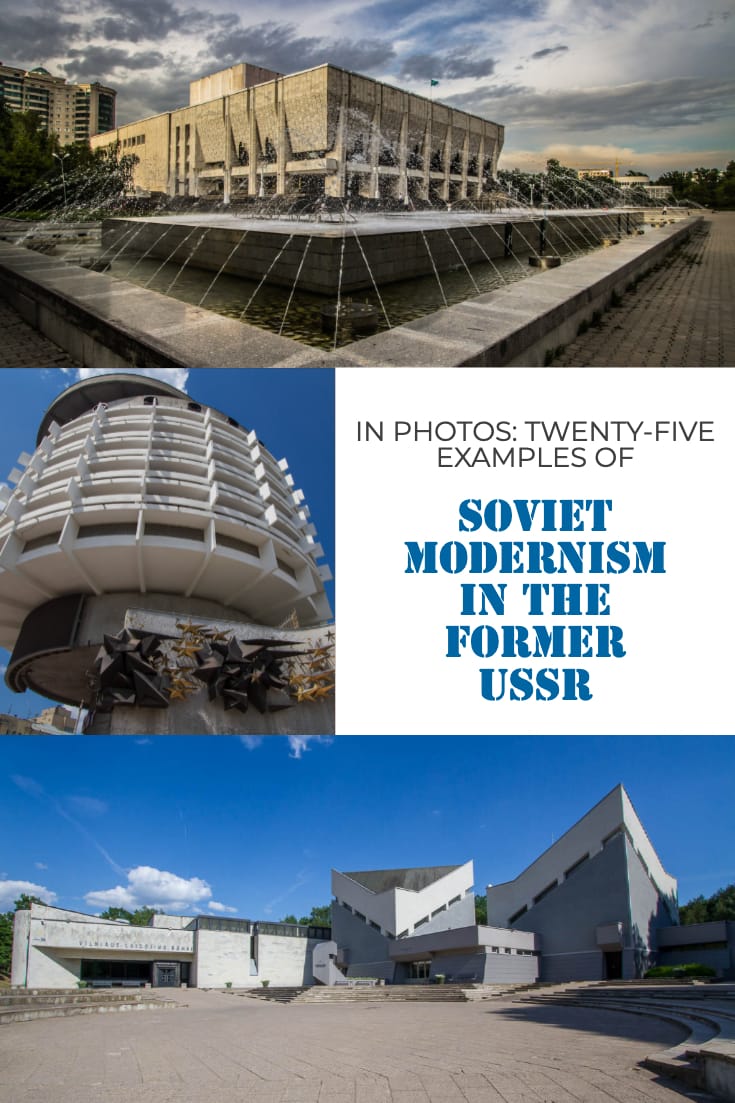

Vilnius Funeral House Ritualas (Vilnius Ceremonial Services Palace)

Vilnius, Lithuania

Completed 1986

Architect Č. Mazūras

Kazakh State Academic Drama Theatre named after M.O. Auezov (Auezov Theatre)

Almaty, Kazakhstan

Completed 1980

Architects O. Baymurzayev, A. Kaynarbayev and M. Zhaksylykov

Belarusian National Technical University (Faculty of Architecture and Construction)

Minsk, Belarus

Completed 1982

Architects I. Yesman and V. Anakin

Ukrainian Institute of Scientific and Technological Research and Development (Ukrainian Institute of Scientific and Technical Expertise and Information and House ‘Flying Plate’)

Kyiv, Ukraine

Completed 1971

Architects Lev Novikov and Florian Yuriev

Vilnius Palace of Concerts and Sports (Sporto Rūmai)

Vilnius, Lithuania

Completed 1971

Architects Eduardas Chlomauskas, Jonas Kriukelis and Zigmantas Liandsbergis

Karen Demirchyan Sports and Concerts Complex (Demirchyan Arena, Sports & Music Complex or Hamalir)

Yerevan, Armenia

Completed 1983

Architects A. Tarkhanian, S.Khachikian, G. Poghosian and G. Musheghian

World Trade Centre Riga (former building of Latvia’s Communist Party Central Committee)

Riga, Latvia

Completed 1974

Architects J. Vilciņš, A. Ūdris, G. Asaris and A. Staņislavskis

Central Library of Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University

Tbilisi, Georgia

Completed 1971

Architects B. Maminayshvili, N. Mgaloblishvili, Z. Kopaladze, S. Kachkachishvili, N. Mikadze, S. Revishvili, A. Sabashvili, D. Chopikashvili and L. Medzmariashvili

Kharkiv State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre named after N. Lysenko

Kharkiv, Ukraine

Constructed 1970-1990

Architects S.N. Mirgorodsky, V.D. Elizarov, N.V. Chuprina, R.N. Gupalo, and A.P. Zybina

Former Central Bus Station

Hrazdan, Armenia

Constructed 1976-1978

Architect Henrik Arakelyan

Salute Hotel

Kyiv, Ukraine

Constructed 1982-1984

Architects A. Miletsky, N. Slogotsky and V. Shevchenko

Yeritasardakan Metro Station

Yerevan, Armenia

Completed 1981

Architect Stepan Kyurkchyan

Bus Station Striyskyi

Lviv, Ukraine

Completed 1980

Architects V. Sagaidakovskyi and M. Stolyrov

Vila Auska

Palanga, Lithuania

Completed 1979

Architect J. Šipalis

Wedding Palace

Lutsk, Ukraine

Completed 1985

Architect Vladimir Moroz

Palace of Pioneers (Palace of Children and Youth)

Dnipro, Ukraine

Completed 1990

Architects Y. Amosov, T. Solodovnik, V. Garsia Ortega and A. Klever

Bus Station

Vanadzor, Armenia

Completed 1976

Architect G. Modzmanishvili

Kharkiv State Circus

Kharkiv, Ukraine

Completed 1974

Architect V. A. Kasyan

SEE ALL BLOG POSTS RELATING TO THE FORMER USSR

CHECK OUT ARCHITECTONICS

Great architecture! Russian buildings seem to always incorporate nice curves.

Indeed! Given the bureaucracy they no doubt encountered, the architects of this era were remarkably creative!

Have you seen any of the bus stops? It seems like I saw some in a book once. Just random Soviet construction in the middle of nowhere.

Yes, quite a few but mostly just in passing as we’ve been on public transport and had no opportunity to stop unfortunately! We have managed to photograph some of them however and there are a few on the Architectonic section of our website (https://www.kathmanduandbeyond.com/architectonic/).

The books you are thinking of are Soviet Bus Stops Volume I and II and like you say, most are in the middle of nowhere!

Excellent article with unique buildings. Thank you for your research. Another fascinating building I stumbled across in this style is the former Soviet concert hall in Talinn, Estonia. Built for the 1980 olympics where the water sports were hosted out of Talinn.

Turns out thr building is also featured in the recent movie Tenet.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linnahall

Thank you for the compliment and you are right about the Linnahall – we’ve spent time in Tallinn looking for Soviet-era structures and this was one of the most impressive. It’s a shame it is in such a terrible state these days but, none the less, it remains impressive.