In search of brutalist and post-war modernist architecture in London

Like many long-term and avid travellers, we have more or less been grounded in our home country of England for the past ten months. Of course, there are numerous frustrations attached to this. We spend a high percentage of my time daydreaming about Soviet-era mosaics in Central Asia, brutalist-style architecture in Skopje and Belgrade, and socialist-era monuments and memorials in Bulgaria, all of which were part of our travel plans for the summer just gone. But, there has been one place that has helped ease the disappointment of not being able to travel overseas and in particular our lust for architecture and that is our capital and largest city, London.

Thanks to the generosity of a good friend, we spent the most recent England lockdown (5th November – 2nd December 2020) in an empty apartment in central London. Unlike the lockdown in March, where you were only allowed to go outside once a day for an hour of exercise, the regulations this time around permitted us to be outdoors for an unlimited amount of time.

This was a green light for us, plus there was no mention of not being allowed to have a camera on your person!

With a packed lunch including a flask of tea (to avoid going in any shops), face masks at the ready and our maps.me app armed to the teeth with locations we had pinpointed using a mix of books, maps and internet sites, we would walk for miles and miles in search of London’s finest brutalist and post-war (World War II) modernist architecture. We were also on the lookout for street art and for the first time, we also actively sought out buildings in the style of Art Deco and early modernism which, in our definition, was anything from the turn of the twentieth century until the beginning of World War II.

For the bulk of this time, we wandered around the city, getting as far as we could on foot before eventually wending our way back to our temporary home around dusk. We walked more than 100 miles (approx. 160kms), occasionally giving our punished feet a rest by making use of the Santander Cycle scheme, aka the Boris Bikes. We made it as far north as Hampstead, got down to Stockwell in the south of the city and Shoreditch and Brompton in the east and west respectively. We traversed some of London’s finest parks, including St. James’s, Hyde and Battersea to get to where we wanted to be and looked around parts of London that would normally be packed with people, especially at the weekends and in the lead up to Christmas. We got to photograph Buckingham Palace with hardly a soul in front of it, shots of London’s busiest streets (Oxford Street, Tottenham Court Road, Carnaby Street etc.) mostly empty, as well as photos of places that are normally bustling with visitors, such as the Horse Guards Parade, the Southbank and Westminster Cathedral, which were all but deserted. It was only when we got away from the centre of London and the City and into the suburbs, that we started to see a resemblance of normal life.

It was a unique, and sometimes eerie sensation, with workmen by far and away making up the bulk of the humans we did come across. When this is all over and everything is back to normal as it is going to be, I think, without question, we will look back on this time we spent in London during the lockdown and consider it to be a once-in-a-lifetime experience that we will (hopefully) never witness again.

Buckingham Palace

As for the architecture, post-war modernism and brutalism emerged during the early 1950s as part of the reconstruction of a badly damaged Britain. Not surprisingly, London was a priority target for German bombing campaigns throughout the war and large swathes of the capital were destroyed during the Blitz (September 1940-May 1941) and again towards the end of the conflict (June 1944-March 1945) when the terrifying V-1 and V-2 rockets were unleashed by the enemy. From housing estates to government premises, military barracks to hospitals and recreation centres to theatres, the use of the buildings we searched for were as diverse as their designs. Having spent years living and working in London in our earlier lives, many of them were already familiar to us but this was the first time we’d paid them any real attention.

We took far too many photos than anyone could possibly need, and of too many buildings to list them all. So, instead, and with reluctance, I am going to whittle it down to some of our favourite modernist and brutalist structures from that period.

What’s more, as mentioned above, Art Deco and pre-war modernism also made it onto our radar for the first time but adding examples of both genres into this post would create architecture-overload. Instead, I have put together a separate post featuring a collection of London’s best Art Deco and early modernist architecture.

I’ve also purposely omitted what is arguably the great brutalist complex in London, the Barbican Estate. It’s not because we haven’t visited it – we most certainly have, on several occasions in fact, and for hours on end but, it is such an incredible place that it warrants a solo guide to its architecture that also includes the Barbican Centre and Golden Lane Estate.

Both brutalist and post-war modernist architecture in London is well documented. It is very easy to find out reams of information about a specific building in the capital either from books or a basic Internet search. Hence, for the best part, I’ve only provided basic facts, although in some instances I have added additional commentary if worthwhile. For every structure, I have added the address, including the post (zip) code and marked them on a map in case you want to go see any of them for yourself.

Map showing some of the best brutalist and post-war modernist architecture in London

You will also notice I have said whether the building is question is listed or not. In brief, if a structure is listed in Britain it means it is protected by Historic England (officially the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England), a non-departmental government body tasked with protecting ancient monuments as well as historic buildings, memorials, parks and gardens etc. There is, of course, a process to go through but once something is listed, it cannot be demolished, extended or tampered with without permission from the relevant authority. In the first instance, this is normally the local council but if a building is of significant historic interest any request will be sent up the ladder to the relevant central government agency. There are three grades; I, II* and II, with Grade I being the most important. As a general rule, buildings have to be more than 30 years old to be listed so, as time goes by, more brutalist and post-war modern buildings are being given either grade II*, or more commonly grade II status.

The Barbican Estate in the City of London was Grade II listed in 2001

Before moving on, I was interested to find out the law in England with regards to photographing buildings, both public and private. In other countries, we’ve either been told outright that we can’t take a photo of a specific building or we’ve been shooed away for doing so. A while ago in London, we got questioned by a guardian (he wasn’t exactly a security guard) when taking a photo of a place of worship. I told him the building in question was a good example of 1960s modernist architecture and that is why I was pointing our camera at it. He didn’t stop me taking the photograph but remained suspicious and even took a snap of us on his phone. During our recent time in London, we took shots of what I would call sensitive buildings, including the MI6 headquarters in Vauxhall and also Hyde Park Barracks. I was a bit nervous about doing so but it transpires that the law in England on the subject is pretty liberal compared to many other places around the world. This article explains your rights in full but the crux of it is that you can photograph buildings (and people) without permission as long as you, yourself, are standing in a public place. There are, of course, other things to consider, such as the definition of ‘public’ property (a pavement is public property, for example, but a shopping centre or a car park is not) but it is probably the reason why you hardly see any NO PHOTOGRAPHY signs on the sides of buildings in London and other parts of the UK.

Some of what we think are the best examples of post-war modernist and brutalist architecture in London

National Theatre

Upper Ground South Bank London SE1 9PX

Constructed 1969-1977

Architect Denys Lasdun

Style: Brutalist

Grade II* Listed

National Theatre

Stockwell Bus Garage

Binfield Rd, Stockwell, London SW4 6ST

Completed 1952

Architects George Adie and Frederick Button (Adie, Button and Partners) with Thomas Bilbow

Style: Modernist

Grade II* Listed

At the time of its construction, Stockwell Bus Garage had the largest unsupported roof span in Europe, which was made using concrete because there was a shortage of steel at the time. It was built at a time when trams in London were being phased out and replaced with buses, of which the depot has the capacity to park 200 or so.

Stockwell Bus Garage

Ministry of Justice

102 Petty France Westminster, London SW1H 9AJ

Constructed 1972-1976

Architects Fitzroy Robinson & Partners with Basil Spence

Style: Brutalist

From 1978 to 2004, 102 Petty France was the main offices for the British Home Office. As well as the Justice Ministry, the building is also home to the Government Legal Department. The structure has been described as “that irredeemable horror” by the prominent art and architectural historian, Nikolaus Pevsner and accused of ruining St James’s Park because it towers above it by the politician and lord, Norman St John-Stevas. Indeed, his full quote was “Basil Spence’s barracks in Hyde Park (coming up later in the post) ruined that park; in fact, he has the distinction of having ruined two parks, because of his Home Office building, which towers above St James’s Park.” Personally, if I had to pick just one building in London and call it my favourite then it would be this one!

Ministry of Justice

30 Cannon Street

30 Cannon St, London EC4M 6XH

Constructed 1974-1977

Architect Whinney Son & Austen Hall

Style: Modernist

Grade II Listed

Originally the London headquarters of the French bank, Crédit Lyonnais, which was acquired by Crédit Agricole in 2003. The building was revamped by Delvendahl Martin Architects between March 2015 and September 2016.

30 Cannon Street

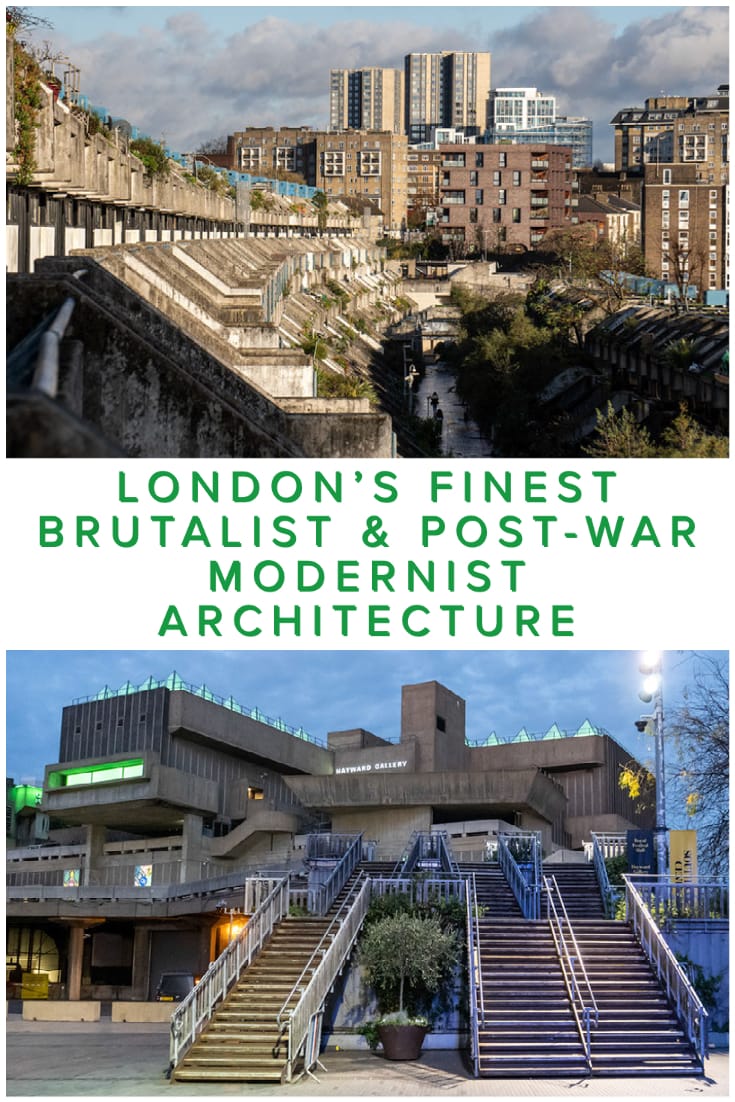

Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate

Langtry Walk, London NW8 0DU

Constructed 1972-1978

Architect Neave Brown for the Camden Architects’ Department

Style: Brutalist

Grade II* Listed

Often just referred to as Alexandra Road Estate or Rowley Way after the main thoroughfare that runs through it, the estate has featured as a backdrop in several movies and television including Spooks, Prime Suspect and Kingsman: The Secret Service.

Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate

45 Park Lane

45 Park Lane, Mayfair, London W1K 1PN

Completed Early 1960s

Architects Walter Gropius, Richard Llewelyn-Davies and Jeffrey Weeks

Style: Modernist

Walter Gropius was the founder of the Bauhaus School in Weimar in 1919 and is widely considered to be one of the pioneers of modernist architecture. In 1965, Playboy rented the building and it became the organisation’s first club in Europe. Playboy left in 1982 after their casino licence was not renewed. Thereafter, the building had various occupants until 2011 when it was revamped by architects Paul Davis + Partners & The Office of Thierry W. Despont Ltd and became the sister hotel to the Dorchester, which is located next door.

45 Park Lane

Kensington and Chelsea Town Hall

Hornton Street, W8 7NX

Constructed 1973-1977

Architect Basil Spence

Style: Brutalist

Chelsea and Kensington Town Hall

Swiss Cottage Library

88 Avenue Road, London NW3 3HA

Completed 1964

Architects Basil Spence, Bonnington and Collins

Style: Brutalist

Grade II Listed

Swiss Cottage Library

Metropolitan Police Forensic Science Laboratory (formerly the Metropolitan Police Central Communications Command Centre)

109 Lambeth Rd, Bishop’s, London SE1 7JP

Completed 1966

Architect Metropolitan Police Architects Department

Metropolitan Police Forensic Science Laboratory

123 Victoria Street

Victoria Street, London SW1E 6DE

Constructed 1971-1975

Architects Cecil Elsom William Pack and Alan Roberts (Elsom Pack & Roberts)

Style: Modernist

Separated by a square on which Westminster Cathedral is located, this development originally comprised two parts – BP House to the right of the cathedral if facing it and Ashdown House to the left.

123 Victoria Street (Ashdown House side)

Battleship Building

179 Harrow Rd London W2 6NB

Constructed 1968-1969

Architects Bicknell and Hamilton for British Rail

Style: Modernist

Grade II Listed

Originally constructed as Paddington British Rail Maintenance Depot and known as Canal House, the building sits adjacent to the Westway Flyover (an elevated section of the A40/London to Fishguard Road) and is surrounded by roads on all sides. It fell into disrepair during the 1990s before being refurbished and converted into office space in 2000 by Allford Hall Monaghan Morris Architects.

Battleship Building

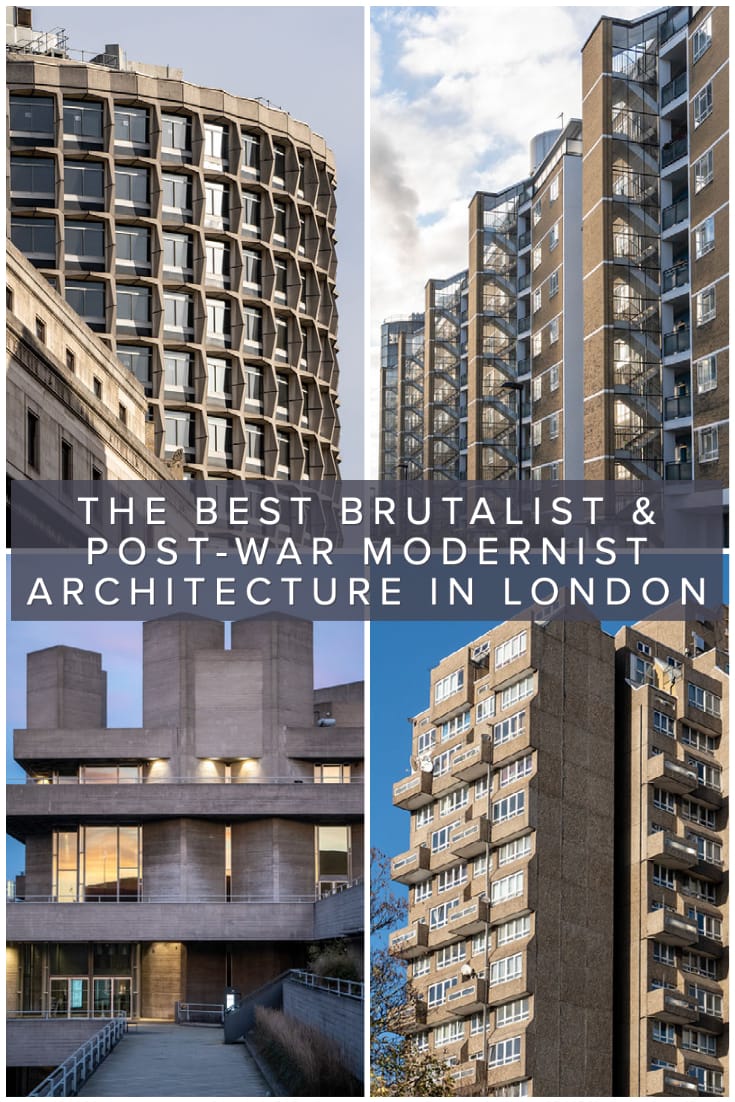

Park Tower Knightsbridge Hotel

101 Knightsbridge, Belgravia, London SW1X 7RN

Constructed 1970-1973

Architect Richard Seifert & Partners

Style: Brutalist

The Development of Tourism Act, 1969 recognised the significance of inbound tourism to London and other parts of the British Isles as an important source of revenue. One of the consequences of the new legislation was the construction of several mega-structure hotels in central London, which were in keeping with the style of the day but not necessarily their historical surroundings. The Park Tower Hotel, which is encircled by the finery of Knightsbridge (including Harrods) is one such example. The St Giles Hotel just off Tottenham Court Road and the InterContinental London Park Lane on Hyde Park Corner would also fall into the same category.

Park Tower Knightsbridge Hotel

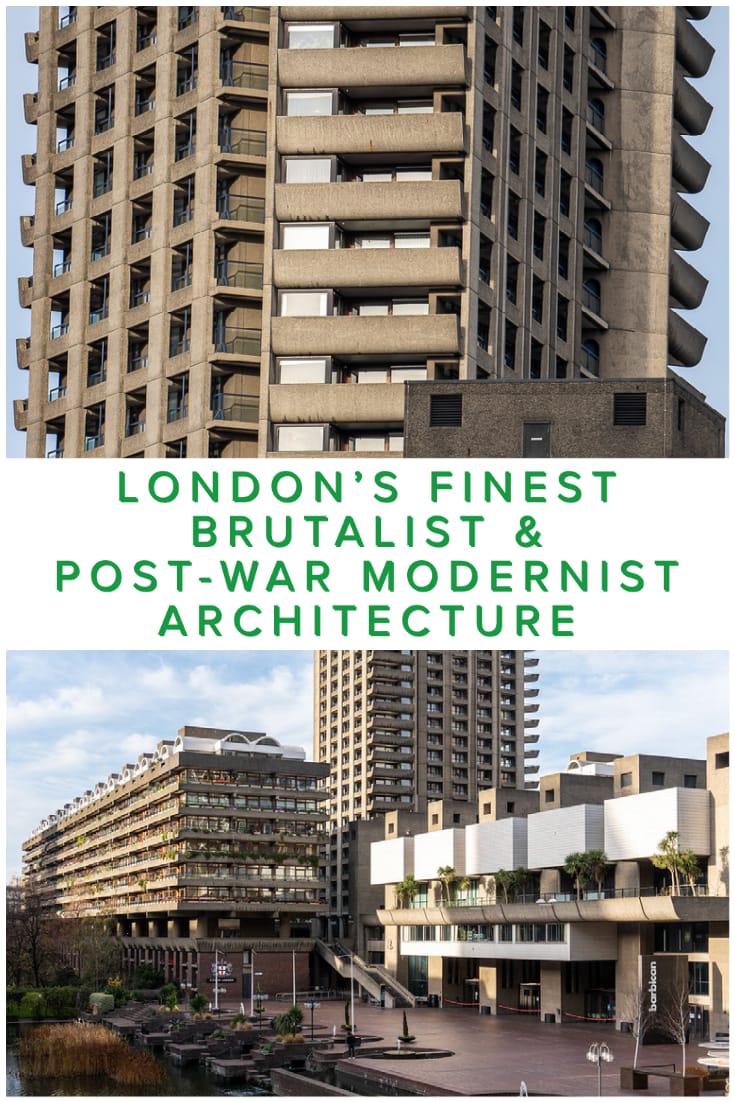

Churchill Gardens

Churchill Gardens Rd, Pimlico, London SW1V 3DS

Constructed 1946-1962

Architects Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya (Powell & Moya Architect Practice)

Style: Modernist

Grade II Listed (Phase I plus the accumulator tower)

This Pimlico estate replaced Victoria terraced housing which was damaged by bombing during World War II. Located more or less opposite Battersea Power Station, the estate is noteworthy for its centralised heating system. Part of the Pimlico District Heating Undertaking, the system began operations in the 1950s and used waste heat from Battersea Power Station, which was pumped under the River Thames via a disused water board tunnel to a thermal store on Churchill Gardens estate. After the power station closed in 1983, the system was eventually converted to gas but the glass-faced accumulator tower remains the largest of its kind in the UK.

As for the estate itself, it was built in four stages over a 16 year period after a contest was held by Westminster City Council to decide the architect. Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya, who were then aged just 24 and 25 respectively, won the contract out of 64 entries for the £4,000,000 housing scheme.

Chaucer House (Churchill Gardens). Constructed 1946-1949 (Phase I)

Churchill Gardens; Anson House (constructed 1952-1957/phase III) (left) and Moyle House (constructed 1957-1962/phase IV) (right)

Hayward Gallery

Southbank Centre, Belvedere Rd, Bishop’s, London SE1 8XX

Completed 1968

Architects Greater London Council Architects’ Department under the leadership of Norman Engleback

Style: Brutalist

Grade II Listed

Hayward Gallery

Baynard House

133 Queen Victoria St, London EC4V 4BQ

Completed 1979

Architect William Holford & Partners

Style: Brutalist

Occupied by the BT Group (formerly British Telecom), the cast aluminium totem pole-like sculpture in the courtyard (below left) is called the “Seven Ages of Man” and is the work of Richard Kindersley. It was commissioned by Post Office Telecommunications and unveiled in 1980.

Baynard House

Minories Car Park

1 Shorter St, Tower, London E1 8LP

Completed 1969

Architects City of London Architects’ Department

Style: Brutalist

Minories was a former civil parish during medieval times. The name is derived from the late 13th century Abbey of the Minoresses of St. Clare without Aldgate, a monastery for Franciscan nuns living an enclosed (separate from the outside world) existence.

Minories Car Park

Brixton Recreation Centre

27 Brixton Station Rd, Brixton, London SW9 8QQ

Constructed 1975-1985

Architect George Finch and Ted Hollamby for the Lambeth Architects’ Department

Style: Brutalist

Grade II Listed

During his first state visit to Britain in 1996, Nelson Mandela made a symbolic and detoured visit to Brixton and used the Rec, as it is known locally, as the venue to address the thousands of supporters who turned up to greet him.

Brixton Recreation Centre

Congress House

23-28 Great Russell St, Bloomsbury, London WC1B 3LS

Constructed 1953-1957

Architect David Du Roi Aberdeen

Style: Modernist

Grade II* Listed

Constructed as the Trades Union Congress (TUC) headquarters, the building was, and still is, considered to be one of the most notable modernist structures erected in the aftermath of the Second World War. The interior, particularly the open-to-the-sky courtyard “Pieta”, where a memorial to trade union members who fell during both world wars (sculptor Jacob Epstein/1958) is the centrepiece, is especially worth seeing but, due to COVID restrictions, we weren’t allowed inside the building on this occasion.

The Dyott Street elevation (bottom left) is now an office development known as The Rookery. The name is derived from the 18th and 19th century colloquial term used to describe a city slum, which in turn is a reference to the cramped, noisy and messy nesting habits of the rook. The area around St Giles, where the Congress House is located, was an especially notorious rookery. The multi-phased refurbishment, which spanned a period of over 20 years, was completed in 2018 and carried out by Hugh Broughton Architects.

“The Spirit of Brotherhood” (bottom right), completed in 1958 by sculptor Bernard Meadows, sits above the building’s main entrance and symbolises the spirit of trade unionism with the weak being looked after by the strong.

Congress House

Imperial Hotel

61-66 Russell Square, Holborn, London WC1B 5BB

Completed 1970

Architect C. Lovett Gill & Partners

Style: Brutalist/Modernist

The original Imperial Hotel at the same location was completed in 1911 and the work of the architect, Charles Fitzroy Doll, who also designed the dining room on board the Titanic. It was demolished in 1966/7 on the premise that it lacked enough bathrooms and was structurally unsound, although it has also been said that the property was the victim of taste and style prevalent at the time.

Imperial Hotel

Brunswick Centre

Bernard St, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 1BS

Constructed 1967-1972

Architect Patrick Hodgkinson

Style: Modernist

Grade II Listed

The Brunswick Centre, a combined residential and shopping centre right in the heart of Bloomsbury, is considered a pioneering example of low-rise, high-density housing.

Smithson Plaza (formerly Economist Plaza)

24 St James’s St, St. James’s, London SW1A 1HA

Constructed 1962-1964

Architects Alison and Peter Smithson

Style: Brutalist

Grade II* Listed

The original London premises of The Economist magazine were bombed during World War II, so the publishers took the opportunity to consolidate their various remaining offices into one single location. Along with the 15-storey Economist Tower, the project included a residential tower and another building for a London-based private bank, Martins Bank. The Economist remained in the tower until 2017, when it relocated to another place near The Strand. The complex was acquired by a new developer and subsequently renovated by architects DSDHA. The wife and husband architect team of Alison and Peter Smithson were considered pioneers of the British brutalism movement that took off during the second half of the twentieth century, and the complex is now named after them.

Smithson Plaza (formerly Economist Plaza)

UCL Institute of Education

20 Bedford Way, Bloomsbury, London WC1H 0AL

Constructed 1970-1976

Architect Denys Lasdun

Style: Brutalist

Grade II* Listed

Denys Lasdun completed two buildings for University College London (UCL), the other being the nearby School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) (below right), which he finished first, in 1974.

University College London

Hyde Park Barracks

20A Knightsbridge, London SW7 1SE

Constructed 1967-1970

Architect Basil Spence

Style: Brutalist

Little over a kilometre from Buckingham Palace, there has been a cantonment at this Knightsbridge location since the end of the 18th century. The current barracks have the provision for around 500 personnel and 270 horses of the Household Cavalry. The controversial residential tower, which is considered an eyesore by many, was designed this way to save space for a parade ground in what was a restricted plot of land. It provides 33 floors of accommodation. There has been talk of the Ministry of Defence moving the regiment to another part of the capital and selling off the site, which is prime real estate but, to date, this hasn’t taken place.

Hyde Park Barracks

Lambeth Towers

74 Kennington Road, London SE11 6NJ

Constructed 1965-1972

Architect George Finch for the Lambeth Architects’ Department

Style: Brutalist

Lambeth Towers

One Kemble Street

Kemble Street, Westminster, London, WC2B 4AN

Constructed 1964-1968

Architect George Marsh of Richard Seifert & Partners

Style: Brutalist

Grade II Listed

One Kemble Street is part of an office complex formerly known collectively as Space House. The other building is called CAA House (Civil Aviation Authority), although the organisation was originally in One Kemble Street when they moved in in 1975. George Marsh, the architect for the project, also designed Centre Point near the junction of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street. Both buildings were developed by the speculative property tycoon, Harry Hyams, who made his fortune generating office space in London during the 1960s and 1970s.

One Kemble Street

Southwyck House

Somerleyton Road, London SW9 8TN

Constructed 1972-1981

Architect Magda Borowiecka for Lambeth Architects’ Department

Style: Brutalist

Part of Somerleyton Estate in Brixton, the building is also known as “Barrier Block” because it was designed as part of the South Cross Route, a planned ring road scheme developed by Greater London Council to alleviate traffic congestion. Construction on some sections of the ring road began in the 1960s but, by the end of the decade, the plans had attracted increasing opposition over the demolition of properties and noise pollution etc. and the project was cancelled in 1973.

Had the scheme gone ahead, the proposed inner-city motorway would have passed directly in front of the “Barrier Block” and the blueprint for the megastructure, which included fortress-like outer walls and tiny windows, was an attempt to shield its residents from the traffic noise and pollution that would have been inevitable.

Southwyck House

Further reading:

If you want to find out more about some of the buildings featured above, some good starting points include the following;

Historic England

Modernist Britain

Modernist London

Blue Crow Brutalist London Map

The Twentieth Century Society (C20 Society)

An organisation that campaigns to protect iconic buildings erected across the UK since 1914.

Manchester History

Contrary to the title, this website features an extensive arsenal of information about all manner of distinctive buildings in the London area.

IF YOU ENJOYED OUR PHOTOS OF LONDON’S BEST BRUTALIST AND POST-WAR MODERNIST ARCHITECTURE, PLEASE SHARE IT…

What an incredible collection! I love how you highlighted the unique beauty of brutalist and post-war modernist architecture in London. Each building tells its own story, and it’s fascinating to see how these styles shape the city’s identity. Can’t wait to explore some of these spots in person!