A single-line train track and the occasional bit of razor wire were the only things that separated Croatia and Slovenia as we drove through picturesque countryside en route to the unassuming village of Kumrovec.

Situated 60km slightly northwest of Zagreb, the settlement only has one claim to fame but, in this neck of the woods, it’s a biggie because Kumrovec is the birthplace of Josip Broz “Tito”, aka World War II resistance fighter (partisan) and (then) future leader of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

The more I learn about Tito, the more I believe he was a decent guy, who had the interest of his nation at heart. I’m sure he had his faults, in fact I know he did, but I’m not alone in this sentiment. Whenever we have the opportunity, we ask people we meet in the region what they think of Tito and, regardless of age, we invariably get a positive response, along with a hint of nostalgia for the man himself and/or the federation he helped create.

Putting it in general terms, Tito’s brand of socialism, known as Titoism, was less rigid and had a more practical approach compared with the communist ideology that was coming out of the Soviet Union at the time. With the blessing of Tito himself, the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, (which was led by Tito!) deemed it appropriate to establish one of the most prestigious schools of political learning in the country in the small village of Kumrovec, deep in the Croatian countryside.

Exterior of the first political school in Kumrovec, which was later renamed Yugoslav Memorial Home

The first political school (politička škola) was opened in Kumrovec in 1975, but very soon it became too small to accommodate the growing number of party members and eager students who descended on the village to attend lectures and conferences on the subjects of socialism and Marxism. And so construction work began on a newer and much larger facility almost as soon as the original one had opened.

With two conference halls, 145 bedrooms (all single-bedded), a cinema, sports hall and a bomb shelter capable of withstanding atomic power among its facilities, the new Politička Škola Josip Broz Tito was far more modern and impressive than its original counterpart. As a side note, Tito himself never got to see the finished building as it wasn’t completed and officially opened until 1981, the year following his death.

Exterior of the second political school in Kumrovec

The building operated as a political school for most of the 1980s (it was also used as a military academy for a short while towards the end of the decade) but became obsolete not long after the beginning of the ethnic-related Yugoslav Wars, which started in Croatia and neighbouring Slovenia around about the same time in 1991 and eventually resulted in the break-up of the Yugoslav state.

During the Croatian War of Independence (March 1991 to November 1995), the building was used to house internally displaced persons (IDPs) from Vukovar, a city in eastern Croatia which was heavily damaged during the conflict. (*)

(*) The Battle (or Siege) of Vukovar lasted 87 days and caused such heavy damage and destruction that it has been compared with the Battle of Stalingrad in Russia in 1942-43.

IDPs from Vukovar (and possibly elsewhere) lived inside the political school until 2003 when they were eventually re-housed. The building has remained empty ever since and at some point in the 2000s, it was put up for sale with a price tag of around €3 million. Interest has been slow and to date the structure remains unsold and belongs to the Croatian Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Having ventured inside the building, I can understand why nobody would want to purchase it. Of all the abandoned places we have seen, the political school in Kumrovec has to be one of the most wretched.

We arrived in Kumrovec mid-afternoon on a lovely autumn day and quickly located the political school. We took a few photos of the structure’s exterior and eventually made our way to the main entrance. The doors were shut tight and there was no obvious way in – the same was true of the large glass doors at the back of the building. Eventually, we found a way in, but on entering the main conference hall, we almost instantly wished that we hadn’t.

Exterior of the second political school in Kumrovec

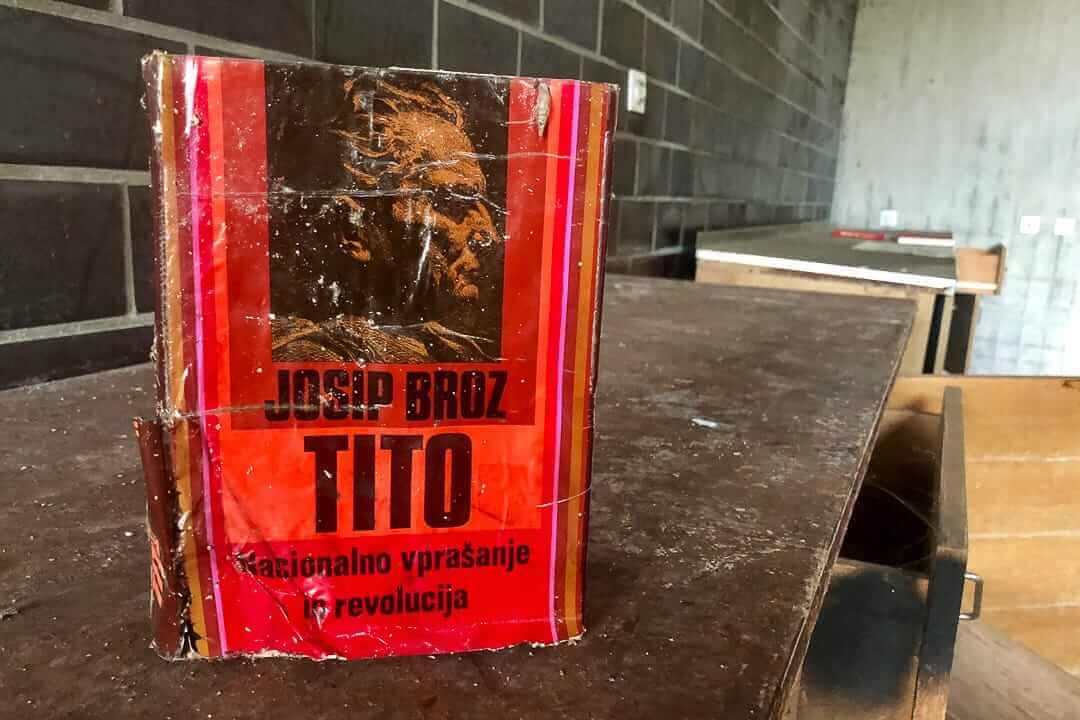

The entire place felt damp. Very damp. Moss and fern were growing from the floor and there was a constant sound of dripping water from the building’s epicentre. After taking time to adjust to what was around us, we started to explore. We walked around the ground floor first, investigating the overgrown bar (where someone had deliberately placed a publication about Tito) and nearby library which was strewn with books and pieces of paper. As we made our way down to the main front entrance and the adjacent restaurant, it became obvious that chairs and books were the only things of any relative worth left in the place. We stopped in our tracks as we heard voices but soon realised they were coming from outside across the road where a few houses were located. During its heyday, the political school was the principal employer for locals from Kumrovec as well as surrounding villages, and I suspect that at least some of those living nearby knew the place intimately and would have some interesting stories to tell.

Above: Interior of the second political school in Kumrovec

We didn’t like the look of the basement, which was extremely dark and dank and so missed out on finding the cinema and probably the gymnasium as well, which we had seen in others’ photos but couldn’t locate on any of the floors we explored. Instead, we headed upstairs to where the bedrooms were situated. As mentioned, each bedroom was a single room and they were all identical in size and faced in a westerly direction. We found foliage here too but at least the upper structure wasn’t as damp as the ground and lower floors.

It didn’t take us long to get creeped out by our surrounding. About thirty minutes if truth be told and even though we were certain we were alone, the place had a sinister feel to it. To that extent, the life we could hear coming from the nearby houses was rather comforting. We eventually returned to the car but I decided to go back in once more as I really wanted to find (and photograph) the gym but it either doesn’t exist anymore, or it was in the depths of the basement. And, although I tried hard to muster the courage to go down the staircase that led to it, in the end, I just couldn’t and so gave up and went back outside into the lovely afternoon sunshine.

Above: Interior of the second political school in Kumrovec

Yugoslav Memorial Home

On a small hill, not that far away, is the original political school briefly mentioned above. Clearly visible from the road below, viewing the exterior of this series of salmon brick-coloured buildings was easy but getting inside proved to be more of a challenge.

Also known as Kumrovec Memorial House, the place was a showcase for Yugoslavian modernist architecture when it opened in 1975 and to this day, even after years of war followed by abandonment, the interior is like a blueprint for 1970s modern living.

We’d seen photos of the inside of the memorial home on the Internet before our arrival in Kumrovec and BADLY wanted to see it for ourselves but, on this occasion, it wasn’t going to happen. The place was well and truly locked up and secure and, ultimately, two things, well three if you count the fact that we never cause any damage in order to enter anywhere, prevented us from getting a closer look at the interior. The first was in the shape of an elderly female caretaker who appeared to live on site with a small army of cats (and the occasional visitors like us) for company. After initially nearly crapping our pants (she appeared from nowhere and gave us a fright), we greeted her and asked if we were OK being on the premises, which she confirmed was fine. We then tried to win her over by making affectionate gestures towards her cats (neither of us are fond of cats) before asking if it was possible to go inside but her reply, consisting of a wagging finger and a shake of her head, indicated there was no room for negotiation, so in the end we bid her good day and headed off around the other side of the main structure.

Exterior of the first political school in Kumrovec

After a bit more roaming around, we eventually did find what looked like a possible entry point but, the second reason for our failed attempt to get inside was down to our lack of pre-urbexing preparation. In the same way that we don’t carry a tripod (see footnote below), neither do we have other basics that more experienced urbexers would consider as standard – a headlamp or a decent torch (not a phone!) and waterproof shoes, for example. We did our first ever deliberate sally into an abandoned building in Kosovo in 2016 wearing shorts and flip-flops and, although we don’t do that anymore, we haven’t progressed, equipment-wise, probably as much as we should have done since that time.

In this instance, the way in was very dark and extremely manky and Kirsty point blank refused to enter and, in all honesty, I didn’t fancy going in on my own. What’s more, in true modern architectural style, the place had plenty of floor-to-ceiling windows and we didn’t want to be spotted (and then landed in the shit) by the caretaker woman we’d encountered only a few moments earlier. I doubt very much if a couple of coochy coos to her mangy cats accompanied by our bestest smiles would have got us out of that one and so, all things considered, we promptly gave up on the idea.

Above: The grounds surrounding the first political school in Kumrovec

If you do want to see what the interior of the Kumrovec’s Memorial Home looks like (it truly is a marvellous time warp from the 1970s), as well as read a good yarn about nearly getting caught inside, then check out the following blog post on My Radiant City.

A final footnote…

Apologies for the poor quality of some of the photos. We know we should carry a tripod with us, but we strive to travel as light as possible and a tripod is one luxury we’ve convinced ourselves we can do without.

READ MORE BLOG POSTS FEATURING ABANDONED PLACES

ARE YOU FASCINATED BY ABANDONED PLACES? PIN THIS POST FOR LATER…

The exposed book is well chosen. Its title is “Josip Broz Tito: The national Question and Revolution”. It consists of selected works attributed to Tito on multi ethnic/multi national states etc. The photographed one is the Slovene edition (published in 1978 and reprinted in 1980) of a book which was published in all the republics and languages of the SFRJ at the time. It is a part of collected Tito’s works thematically grouped in 5/7 volumes.

https://bukvarna.eu/zgodovina-slovenije-bivse-jugoslavije/josip-broz-tito-7-knjig

In the language of Tito’s epoch you could say you have seen the theory (the book) and the praxis (the ruined building) in one place-time. Funny is that I cannot find this book in the libraries of the Faculty of social sciences or Faculty of art of the University of Ljubljana. It is available in many other Slovene libraries though.

Thank you for your very informative comment Bojan. We suspected that the book was deliberately positioned where it was. We’ve seen similar before – books about Lenin, for example, placed where they can clearly be seen in abandoned locations in the former Soviet Union. It’s interesting to know the background behind the collection of works and as you say, strange that you cannot find a copy in, what I am assuming, are important libraries in Ljubljana.

Thanks again for the wonderful information, it definitely adds to the post!