At first glance, Zagreb feels more like a typical Central European capital than a Balkan one. With a mix of Gothic, Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Classical designs, you could be forgiven for thinking you were in Vienna or Budapest. But despite its historical past, these days Zagreb is home to one of Europe’s youngest populations imparting a vibrant atmosphere on its streets.

Museums and art galleries aside, you could cover Zagreb’s traditional attractions in a day. As a result, many travellers don’t linger in the Croatian capital. But ditch the guidebook and scratch below the surface, and you will find there is much more to discover. These are words we find ourselves saying a lot, but ones that are part of our travel ethos as we continually seek less conventional sights.

Many guides to alternative Zagreb mainly feature cool bars and a selection of Zagreb’s many quirky museums: the Museum of Broken Relationships, Zagreb 80’s Museum, and the Mushroom Museum to name a few. However, our guide has a heavy bias towards street art, architecture, monuments, memorials and abandoned places.

For convenience, I’ve divided the places of interest into four areas:

North of the Sava River

South of the Sava River/Novi (New) Zagreb

Away from the city centre

Mount Medvednica

Everything mentioned below is marked on the map. What’s more, all the places detailed in the north and south of the Sava River sections of this post can be accessed on foot. Beginning with the street art in the Upper Town, which is the furthest point north, the locations are listed in a logical order should you want to walk from place to place. Dugave is the most southerly point and from here it is easy to take a tram or a bus back in the direction of the train station and the Upper Town. At a push, it’s possible to see all the places mentioned in these two sections in one day but spreading it over two days would be less punishing on the feet.

Places of interest away from the city centre and on Mount Medvednica will require some form of transport but can be reached using a combination of trams and buses. Public transport options are listed in the relevant parts of the post.

Alternative things to do in Zagreb: North of the Sava River

This is where most visitors to the city spend their time because it is where the Upper and Lower Towns, in other words the old parts of Zagreb, are located.

Street art in the Upper Town

Zagreb has some excellent street art and although the Upper Town isn’t especially renowned for it, there are one or two pieces worth looking out for if you are there taking in the area’s other attractions. We spent a disproportionate amount of time searching for what is possibly Zagreb’s best-known (and largest) mural, a giant whale painted by French artist Etien in 2015. We eventually located it on the building on Gradec plateau, hidden away behind a lot of scaffolding and hard to see. I understand that, as a result of the renovation work on the building, the whale is no longer. The same is also true about a huge 3D turtle which Etien created on the plaza floor a year later, but there are other pieces of street art in the vicinity and it’s a matter of wandering around and seeing what’s there.

1 Ilica Street

Overlooking Ban Jelačić Square, Zagreb’s central focal point, 1 Ilica Street dates back to the late 1950s and was the first skyscraper in the city as well as the tallest building in Yugoslavia at the time of its construction. It is colloquially known as Neboder, which translates as “Skyscraper”. These days the structure is rather unassuming but it is worth stopping by for its historical value and glass facade.

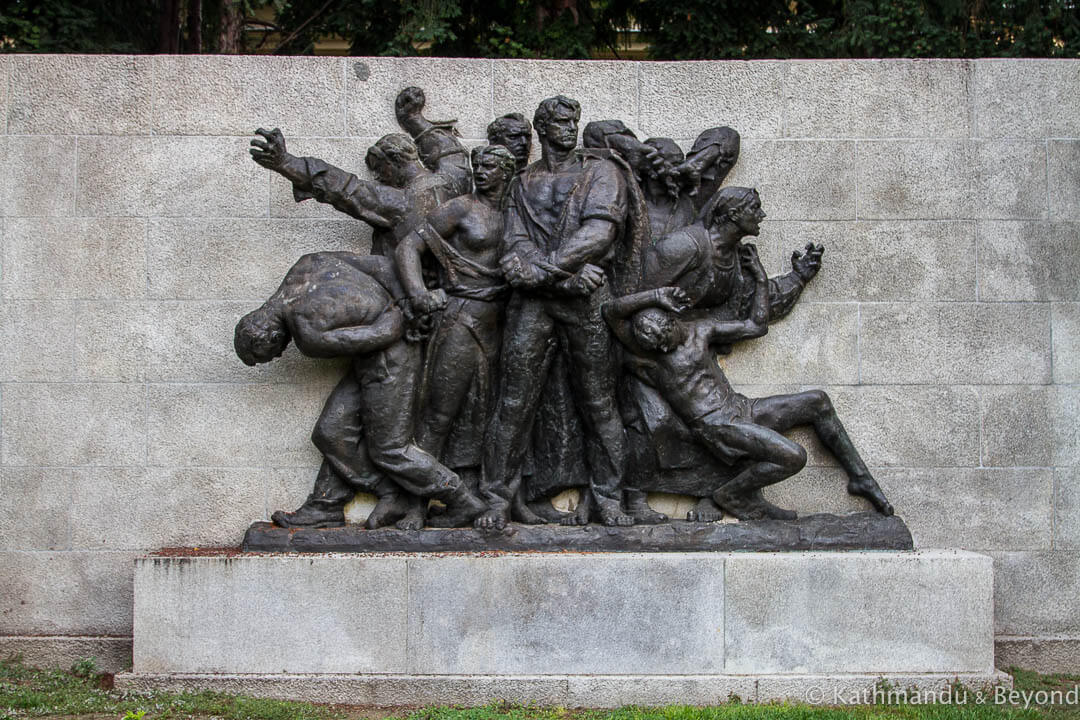

Shooting of Hostages

Croatia was initially an Axis puppet state during World War II, in other words, allied with Nazi Germany, and Zagreb was the centre of the Croatian fascist organisation known as Ustasha. Eventually, the city was taken by the anti-Axis Yugoslav Partisans (led by Josip Broz Tito) and the Shooting of Hostages monument is dedicated to the city’s 7,000-plus citizens who were murdered by the Ustasha during that period. Erected in 1954 and in the style of socialist realism, the Shooting of Hostages monument is a short walk south of Ban Jelačić Square. The sculptor was Croatian-born Frano Kršinić, who was also responsible for several other significant works within Yugoslavia, including a large statue of Tito that once stood in the main square in Užice (Serbia) but is now situated in the city’s national museum.

Branimirova street art wall

Branimirova street art wall is a sanctioned street art area that stretches for about 500 metres along a wall that partitions the street from the city’s railway station. It’s been there at least since 2015, which is when we first visited the city, and although some of the murals were looking a little washed-out when we returned in 2019, there is some imaginative artwork to pursue. Because the pavement is quite narrow, much of the work is best viewed from across the other side of the road.

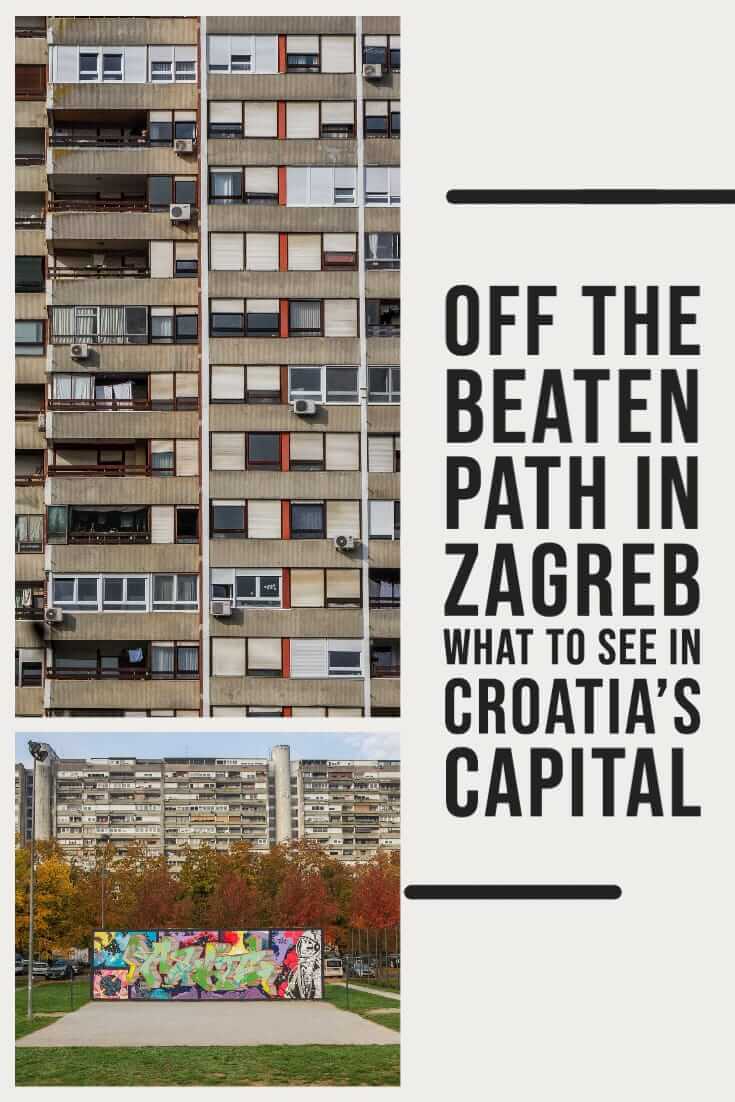

University of Zagreb Student Centre

Heading west of the railway station, past the city’s botanical gardens gets you to the University of Zagreb Student Centre. The reason to come here is to see yet more street art. There is absolutely loads of it and, personally, I thought this was the best of all the urban art we saw in the city. There are a couple of student-orientated cafes on campus should you want a rest before delving back into the colourful street art scene.

Street art near the University of Zagreb Student Centre

I did warn you that the Zagrebian street art scene was pretty prolific and just over the road from the student centre is another area with a healthy stash of creative murals, some of which are quite large. Two of the most impressive murals are by Croatian artist, Lonac.

Zagrepčanka building

Moving away from street art (for a bit, anyway …), socialist-era modernist architecture becomes the primary focus the closer you get to the Sava River. The first building worth checking out if this genre of architecture interests you is the high-rise office building called Zagrepčanka. Ranked either the 1st or 4th tallest building in Croatia (depending on whether you count the rooftop 109-metre radio mast or not), this otherwise 94.6-metre structure was completed in 1976 and extends over 27 levels. Less than a decade after completion, there were issues with large marble tiles falling away from the building’s facade and, for a time, employees had to enter via a makeshift tunnel made of scaffolding and wooden planks. Work to repair the structure has been ongoing for quite some time and is still not completely finished. A staggered race up the building’s 512 steps in aid of Croatia’s Addiction Awareness Month has been held annually since 2012. Funnily enough, the race is called Zagrepčanka 512!

Vjesnik building

Continuing southeast along busy Savska Road, the next Yugoslavia-era building to come in to view is the Vjesnik building. Vjesnik was a Croatian state-own newspaper which began life as an illegal publication for the Communist Party of Croatia/Yugoslav Partisans during World War II when the country was under the control of the Ustasha. Post-war Vjesnik maintained its standing as a newspaper of repute and was widely read throughout Yugoslavia. But, not long after Croatia gained its independence in the early 1990s, the paper came under the control of Franjo Tuđman’s Croatian Democratic Union Party, the country’s ruling power from 1990 until 2000, and it soon acquired a reputation as a pro-government publication. Hence, Vjesnik’s circulation steadily dwindled and this coupled with financial difficulties resulted in the paper ceasing to operate in the first half of 2012.

The modernist-style building dates back to 1972 when the paper’s popularity was at a high. The 15-storey high-rise is still in use but I’m not sure who the current occupiers are.

Richter’s skyscrapers

Often referred to as the “Rockets” because of their shape, Richter’s skyscrapers are part of a socialist-era urban development on the fringes of Zagreb’s Lower Town. The three towers are named after Vjenceslav Richter, the lead architect on this 1960s project. Designed in brutalist style, the original concept for the tower blocks was modified by the architects after the 1963 Skopje earthquake as a precautionary measure against a similar incident happening in Zagreb. I haven’t looked into how many serious tremors have affected the city since that time but as recently as March 2020, the Croatian capital was hit by an earthquake measuring 5.3 on the Richter scale. It would appear from this article that the towers were more or less unscathed by the quake, which was not the case for some of the other structures in the city, and that the residents were quite grateful to the architects for their foresight in altering their plans.

University Computing Centre

On the road leading down to Kockica (see next section), this early ‘70s building is of note as a good example of Yugoslavian modernist architecture.

Kockica

Translating as “Small Cube”, this fantastical structure was originally built to accommodate the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Croatia. Situated on the embankment of the Sava River and looking across to Novi Zagreb, construction on the site started in 1963 but was delayed when the river flooded a year later. It was eventually completed in 1968 and acquired its nickname from locals not long thereafter. Foolishly, we didn’t attempt to visit the interior of the building which, by all accounts, is decorated with some wonderful socialist-era mosaics and paintings as well as a metal tapestry from the same period. Today, the ten-storey structure is jointly occupied by the Ministry of Maritime Affairs, Transport and Infrastructure and the Croatian Ministry of Tourism and is listed as a cultural heritage site.

Croatian Radiotelevision building

The headquarters of Croatia’s public broadcasting company has a commanding position on Slavonska Avenue, Zagreb’s longest street, and was the last building of note that we spotted before crossing Most Sloboda (Liberty Bridge) into Novi Zagreb. Often simply referred to as HRT, the broadcasting organisation has been around since the mid-1920s when it was known as Radio Station Zagreb but this particular building dates to 1975.

Alternative things to do in Zagreb: South of the Sava River/Novi Zagreb

Crossing the Sava River brings you into Novi (New) Zagreb, a socialist-era planned suburb of the city that didn’t come into existence until after the end of World War II. Although predominantly residential, the huge concrete tower blocks and other infrastructure necessary to service the various districts is interspersed with an abundance of green space and spending time here will show you a side of the city that is simply not on most visitor’s radar.

Museum of Contemporary Art

If there is a conventional tourist attraction in Novi Zagreb then it is the Museum of Contemporary Art, the largest museum in the country. The decision to move the museum to its new location was made in 1998 and the building was designed by Zagreb-born architect, Igor Franić. The gallery eventually opened in 2009. We haven’t been inside as art museums aren’t really our thing but, given its size (14,600 sq. metres) and the amount of art on display, you’ll probably need at least half a day to do it justice if you do decide to visit.

Zagreb Fair

We find that trade fairs in the former Yugoslavia are always good hunting grounds for modernist and brutalist architecture and the one in Zagreb falls into that category. Although the history of a trade fair in the city goes back to the middle of the 13th century, the pavilions in Novi Zagreb date back to 1956 and thereafter. Getting inside the grounds proved a little bit tricky for us as there was an exhibition going on and we couldn’t get past security. This was disappointing as some of the best pavilions from an architectural standpoint, such as Pavillon 40, a modernist structure by Ivan Vitić who was the architect responsible for Kockica mentioned above, are beyond the gates of the compound. Still, there is enough to see just by walking up and down Dubrovnik Avenue to make Zagreb Fair a justifiable stop when exploring Novi Zagreb.

Super Andrija

Super Andrija is a Goliath-like residential building situated in the heart of the Novi Zagreb neighbourhood of Siget. Why it is, rather oddly, called Super Andrew (Andrija translates as Andrew) has remained a mystery since its completion in 1973. Some say it is named after the main designer of the structure, who passed away before the project was completed. Another theory is that the name honours a workman who died while labouring on the site and even a high-ranking Yugoslavian general, who resided there and had the given name of Andrija, has been thrown into the mix. Whatever the reason, this huge apartment block is mightily impressive and not to be missed if super-sized housing projects impress you as much as they do us!

Church of the Holy Cross

The rest of Siget is pretty interesting as well. Strolling through the neighbourhood reveals plenty more socialist-era architecture including yet more high-rise buildings and also several garage units that we thought were wonderfully symmetrical. One of the most striking buildings we came across while in Siget, however, was the Church of the Holy Cross, which is about a 15-minute walk west of Super Andrija. I can’t make up my mind if this Catholic house of worship, which was constructed between 1971 and 1982, is modernist or brutalist in design but it certainly grabs your attention and is set off nicely by the line of tower blocks that stand nearby.

Mamutica

Residential skyscrapers aside, we didn’t find anything especially interesting in Sopot, which is the neighbourhood directly to the east of Siget but if you keep walking you reach the urban settlement of Travno, one of the most densely populated places in all of Croatia. The main reason for this density of people is the existence of Mamutica, one of Europe’s largest apartment blocks. There are reportedly 488 apartments in Super Andrija. By comparison, Mamutica consists of 1,169 units, which are home to around 5,000 inhabitants. Mamutica is one year younger than Super Andrija and was completed in 1974.

As for the name of the building, this one is easier to explain: The urban planner behind the design, Miroslav Kollen wanted to call the structure “Tratinčica”, the Croatian word for “daisy” because before building work commenced, the area was a large meadow. But locals decided to call it “Mamutica” which is the Croatian word for female mammoth and, in this instance, the residents got their way and the name stuck. All things considered, “mammoth” is a far more appropriate name than “daisy”!

The complex actually comprises of two buildings, “big” and “little” Mamutica and to really appreciate this concrete giant, you either need to be very close and gaze up and along at the structure’s seemingly never-ending, and countless, number of windows and balconies, or get as far away as you can to realise the scale.

The Church of Saint Luke the Evangelist

This boxy church is just beyond the main carpark for Mamutica and blends in perfectly with its surroundings. Constructed in 2008, the church is a relatively new addition to the Travno neighbourhood skyline.

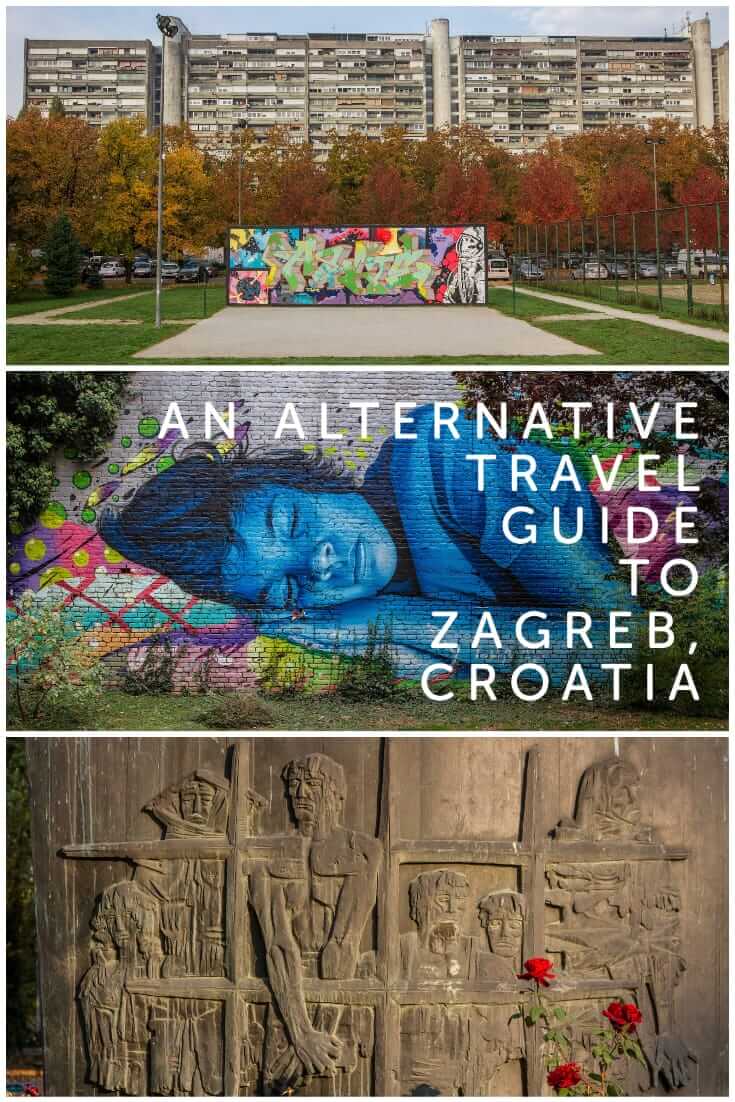

Dugave

We found quite a bit of street art while wandering around Novi Zagreb but the highest concentration was in Dugave, the district directly south of Travno. There is also a big park in the centre of Dugave, making it one of the most desirable places in which to live in Novi Zagreb. Much of the street art here was painted as part of the same project that created the Branimirova street art wall and Dugave received its colourful makeover in 2011 but we suspect that some of the pieces are more recent additions.

You can get back to Zagreb’s main train station from this point by taking bus #220 from bus stop Hribarov prilaz.

Alternative things to do in Zagreb: Away from the city centre

Monument to the Fallen of Ciglenice

Located to the west of the city centre, in a small park known as Pravednika među Narodima, this 9-metre bronze spomenik (Tito-era World War II-related monuments and memorials in the former Yugoslavia) was erected in 1972 and is dedicated to 65 members of the Ciglenica workers’ cultural society who perished during the fight against fascism during World War II. The headquarters of the society, which was formed in 1938, used to be nearby the park in which the memorial is located. It is the work of Croatian sculptor, Tomislav Ostoja.

To reach the Monument to the Fallen of Ciglenice on public transport take bus 118 from the bus stop called Trg Mažuranića, close to the National Theatre. The nearest bus stop to the monument is Zagorska and bus #109, as well as bus #118, also stops there.

Cultural Centre KNAP/Peščenica Culture Centre

Cultural Centre KNAP is situated in the Zagreb neighbourhood of Stara Peščenica (part of a larger district known as Peščenica – Žitnjak). The reason to come here as a tourist is to see the large concentration of urban art that adorns the centre’s exterior walls and inner courtyard. Peščenica was one of the first areas in the city where this style of art flourished (circa the 1990s) and the centre has been supporting street art and graffiti artists for a number of years. The cultural centre has even produced a book featuring 200 works by 95 different artists, which can be purchased on the second floor of the building.

To reach Cultural Centre KNAP/Peščenica Culture Centre on public transport there are a number of buses and trams you can take. The closest bus stop is Trg Volovčica where bus #215 halts. Alternatively, tram stop Ivanićgradska is 550 metres away and is served by tram numbers 2,3, 6, and 13. Trams #2 and #6 depart from Glavni Kolodvor (the main train station).

Monument to the December Victims of 1943

This abstract sculpture in the Dubrava neighbourhood of the city remembers 16 anti-fascists who were hung by the Ustasha on 20th December 1943. The hangings were a swift response to a successful attack by Partisan fighters on a series of German ammunition depots located to the north of Zagreb which took place on the evening of 18th December. Those responsible for the raid were not the ones put to the gallows, however. Instead, 18 civilians, whom the Ustasha already had under lock and key as a kind of insurance policy against such an attack, were transported, without trial, to the spot where the monument now stands and crudely hung from butcher’s hooks attached to wooden poles. During the process, two of the hostages managed to escape under the cover of darkness. The reaction to the executions was one of solidarity among many of Zagreb’s citizens and lots of the Christmas trees that year were decorated with 16 candles in memory of the victims. Even the German high command in Zagreb expressed their horror at the killings and made it clear that the atrocity had nothing to do with them.

To reach the Monument to the December Victims of 1943 on public transport take tram #4 from Glavni Kolodvor and alight at Dubrava stop.

Monastery of Herzegovinian Franciscans

Very close to the Monument to the December Victims of 1943 is another of Zagreb’s modern churches. It was built between 1993 and 1995 and is the work of Zagreb-based architect, Stjepan Antolić.

Dotrščina Memorial Park

Many of the victims associated with the Shooting of Hostages monument mentioned above were executed in the Dotrščina forest on the outskirts of the city. Between 1941 and 1945 in the region of 7,000 anti-fascists, Roma and Jews were murdered by Ustasha and German forces and a handful of monuments in various locations throughout the forest commemorate the atrocities that took place.

The opening ceremony for the memorial park took place in 1968. One of the designers involved in the initial project to landscape parts of the forest was Vojin Bakić, a talented Yugoslavian sculptor who would later be responsible for a number of prominent spomeniks throughout the region, including the now-abandoned Monument to the Uprising of the People of Kordun and Banija in Petrova Gora (Croatia), ‘Circles’ in Šumarice Memorial Park (Serbia) and the Monument to Ivan Goran Kovačić in the village of Lukovdol (also Croatia). Bakić’s family were of Serbian ethnicity and along with his four brothers, he was arrested in 1941 by the Ustasha and sent to a prison camp. His brothers were later executed and Bakić himself only escaped the same fate because his teacher at the Art Academy in Zagreb where he studied, Frano Kršinić, personally intervened at the highest level.

Path to Martyrdom by Vojin Bakić was the first monument to be erected in the forest in 1968. The other memorials were added in the 1980s, a decision influenced by the fact that the city of Zagreb was awarded the prestigious Order of the People’s Hero, a Yugoslav gallantry medal, and the title of Hero City on 7th May 1975. The other memorials are the Valley of the Graves, the Monument to Revolutionaries Before the War, the Monument to the Fallen in Zagreb Liberation and the Monument to Zagreb Citizens Killed in World War II.

Neglected and all but forgotten after the fall of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, the memorial park is relatively well maintained these days and, the cultural significance aside, the forest is a pleasant place for a stroll if you are inclined to make it this far out of the city.

There are several ways to reach Dotrščina Memorial Park by public transport but all require at least one change. The most straightforward is to take tram #4 to Dubrava stop (the same stop as for the Monument to the December Victims of 1943 mentioned above), and then catch bus #232 to Svetošimunska stop. From there it is less than a five-minute walk to the park entrance.

The closest bus stop to the park is Dotršćina, served by bus #205 which heads into the suburbs and is unlikely to be of much use to the casual visitor.

Alternative things to do in Zagreb: Mount Medvednica

Just north of Zagreb, Medvednica is a lush escape from the city. Much of the area is a nature park and there are some good opportunities for hiking along several well-marked trails. From a sightseeing standpoint, the medieval fortress of Medvedgrad on the southern side of the mountain is the main attraction. But, as this is a post about alternative things to see and do in Zagreb, I’m going to focus on two lesser-visited locations instead, both of which have long been in a ruinous state.

Vila Rebar

Not too far from the Bliznec entry point to Medvednica, the foundations of Vila Rebar date back to the 1920s when there was a hunting lodge on the site. The actual villa was constructed in 1932 and during World War II, the Croatian dictator, Nazi sympathiser and founder of the Ustasha, Ante Pavelić, used the manor as his home. A series of tunnels, that are still part-accessible, were added to connect the property with military bunkers located in the nearby hills. Some of them also acted as escape tunnels. After the war, the premises were first converted into a children’s resort and thereafter into an upscale hotel and restaurant called Hotel Risnjak. The place was ravaged by a fire in 1979 that some say was started by a disgruntled employee, and has been abandoned ever since. Both the villa and the tunnels are said to be haunted and it is believed that rave parties were held there in the 1990s.

To be honest, there isn’t that much left to see at Vila Rebar. You can poke around the remains of the above-ground parts of the villa and it is also possible to enter some of the tunnels, some of which go on for quite some way. But, rather you than me – they are very dark and apart from the odd bit of eerie street art, there is nothing to see. There are also the ghost stories to consider and the possibility of bumping into a bear. Brown bears still roam the forests of central Croatia and although it is unlikely they would ever venture this close to civilisation, the fact that Medvednica roughly translates as “bear mountain” should be taken as a warning!

To reach Vila Rebar on public transport, first take tram #14 to Gracani, which is the last stop, and then tram #15 to Dolje, which is also the last stop on that route. From that point, it is about a 15-minute walk to the location.

Brestovac Sanatorium

Further up the mountain, Brestovac Sanatorium is an enchanting series of ruins that consist of the former sanatorium and several smaller outlying buildings that are in an equally ramshackle state as the main structure. Dating back to the first decade of the 20th century, the infirmary was established to look after patients who had tuberculosis, a disease that was rife in many parts of Europe at that time. There is an interesting love story attached to the hospital involving its major benefactor and a well-known Croatian actress but given we have written a more detailed post on the subject, I’m not going to divulge any more details about it here. The post also includes more photos and practical information on how to get to the location using public transport.

IF YOU ENJOYED OUR GUIDE TO ALTERNATIVE THINGS TO DO IN ZAGREB, PLEASE SHARE IT…