How the countries of the former Yugoslavia gained their independence and the conflict it caused

In our search for spomeniks, we have travelled extensively through all of the Balkan countries and autonomous regions that used to make up Yugoslavia. In so doing, we have come across many reminders of the so-called Balkan Wars, also known as the Yugoslav Wars, fought in the 1990s and we have tried to unravel the various causes and consequences of these wars. This backgrounder is a summary of this troubled period in the history of the Balkans but be warned: trying to unravel what happened, and why, is like trying to solve Rubik’s cube if you are monochromatically colour blind! Basically, there were two opposing forces at play – religion and ethnicity – both dominated by conflicting power politics and personal egos and some tensions are still unresolved.

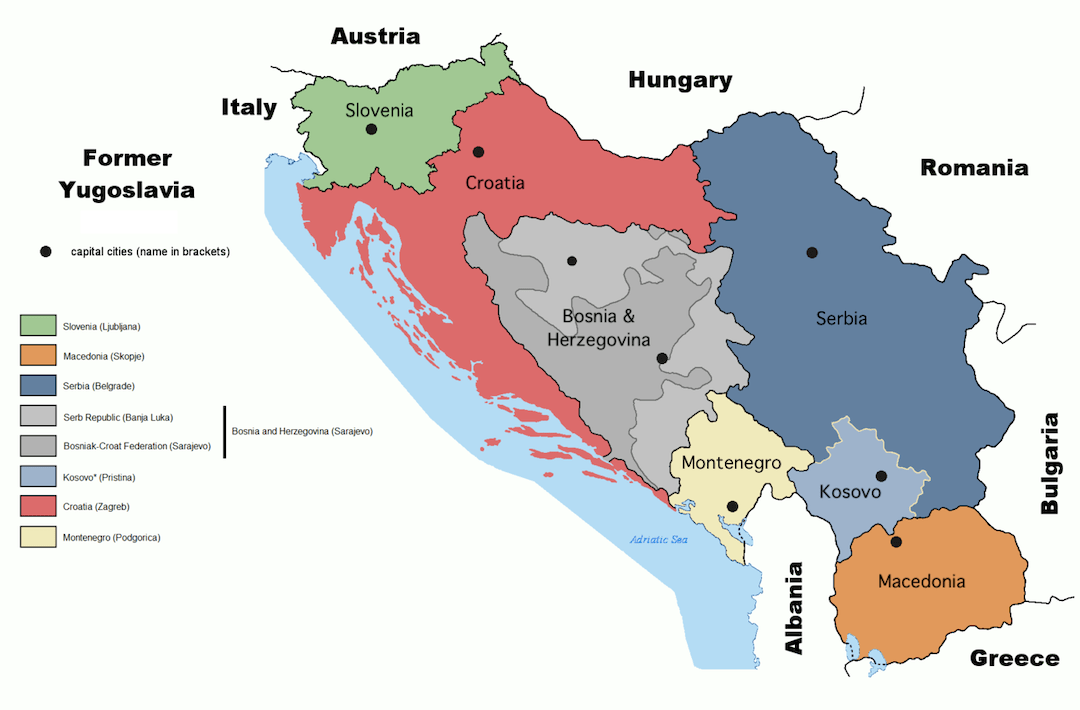

Map of the former Yugoslavia (source)

Background to the Balkan Wars

Although not part of the USSR, Yugoslavia was an alternative interesting experiment in social engineering based on the communist principles laid down by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in 1848. Originally named the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, the country was formed in 1918 under the rule of the Serb dynastic king, Peter I. Peter’s son, King Alexander 1, renamed the country Kingdom of Yugoslavia (‘land of the southern Slavs’) in 1929 and Yugoslavia survived as a kingdom until WW2 when it came under attack by Nazi Germans. In 1941, the then king, a youthful King Peter II, fled to London and, eventually, the United States where he died in 1970.

In the meantime, the resistance movement in occupied Yugoslavia grew under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito, a Croatian communist revolutionary and military man, born in Kumrovec, who had fought in WW1 and was involved in some of the battles of Lenin’s post-1917 Russian Revolution. Tito pulled together the various factions of the Yugoslav resistance movement, collectively known as the Partisans, and emerged in 1945 as the leader of the country, abolishing the monarchy at the same time. From 1945 until his death in 1980, Marshall Tito ruled the country, some say as a benevolent dictator, and imposed his own less authoritarian ideology of communism, although not without its purges. Stalin tried to place Yugoslavia under Russian control but Tito resisted these manoeuvres and throughout 1948-49, major differences of opinion between Tito and Stalin opened up, the Tito-Stalin split. One result of this split was that Tito was able to request aid from western sources to help shore up the economy of Yugoslavia and, under his direction, Yugoslavia blossomed.

Marshal Tito and the Spomeniks

Unlike Stalin, Tito was not interested in developing a personality cult but he was a keen supporter of engendering patriotic feelings towards Yugoslavia, that is, building a Yugoslavian identity rather than aligning identity with an earlier national region such as Serbia or Bosnia. To this end, Tito fostered artistic freedom in literature, art, film and music. He also supported the Soviet Modernism architectural style and the creation of many statues, monuments and memorials depicting those awarded the Order of the People’s Hero of Yugoslavia, the sites of WW2 battles and other places of heroic action, and places of destruction such as the Nazi concentration camps on Yugoslav soil. Many of the monuments, known as spomeniks, the Serb-Croatian/Slovenian word for monument, are large abstract creations meant to symbolise Yugoslavia’s resistance to the German occupation during WW2 but some say they embody more than that – a national spirit, a symbol of hope for the future, a testament of triumph. Whatever you think they represent, they are unique to the countries that make up former Yugoslavia and a testament to Tito and his success at bonding people from different ethnic sources, Slav and non-Slav, and religions, Christian and Muslim.

Unfortunately, these divisions began to resurface after Tito’s death in 1980, culminating in a series of savage wars the like of which Europe had not seen since the end of WW2.

Declarations of Independence and the Beginnings of the Balkan Wars

In common with what was happening throughout the USSR, the 1970s and 1980s saw a re-emergence of national and ethnic sentiments throughout the member states of Yugoslavia and, in 1987, a Serbian communist politician, Slobodan Milošević, was sent to calm the growing unrest between Kosovar Serbs and Kosovar Albanians in the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo. Instead of calming the situation, Milošević inflamed it by strengthening Serb control over Kosovo thus starting a policy of Serb dominance not only over Kosovo but elsewhere, particularly in Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia. As a result, subsequent moves towards independence by these countries were forcibly rebuffed by the Serb government in Belgrade and, ultimately, caused a series of regional wars that resulted in the break-up of Yugoslavia and the emergence of six independent countries: Slovenia, Macedonia, Serbia (coupled with Montenegro proclaimed as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia), Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro. Two Socialist Autonomous Provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina, were also declared and even today, their autonomous status is disputed.

Slovenian Independence War and Macedonian Declaration of Independence, 1991

It can be argued that the breakup of Yugoslavia started when the Slovenian government in Ljubljana, encouraged by the impending dissolution of the USSR and backed by the positive result of a December 1990 independence referendum, asserted its independence in June 1991 thereby initiating the Ten-Day War with Serbia. The Serb-dominated Yugoslav People’s Army (Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija, JNA) attempted but failed to quell the rebellion and in June 1991 Slovenia broke away from Yugoslavia and became an independent country. Macedonia, in the south, quickly followed suit and peacefully became the Republic of Macedonia a few months later (September 1991).

Croatian War of Independence, aka Homeland War,1991 – 1995

Along with the Slovenians and Macedonians, the Croatian government declared independence in 1991 but this was opposed by the indigenous Croat Serbs, backed by the Serb JNA. The subsequent 87-day Battle of Vukovar, started in August 1991, has been likened to the Siege of Stalingrad for brutality and ferocious warfare and resulted in the destruction of 90% of the city. Between October 1991 and May 1992, the JNA besieged Dubrovnik in southern Croatia resulting in several hundred deaths and the displacement of 15,000 people. Similarly, the JNA also bombed the nearby Croatian seaside resort of Kupari built for and frequented by elite Yugoslav military personnel before the Croatian war. In October 1992, the JNA accepted defeat and withdrew its forces from Croatia, but this withdrawal did not end the Croatian War of Independence.

The Croatian conflict continued as an internal (civil) war for another three years between the majority Croatians (70%) and minority Croatian Serbs (12%). Under the military leadership of a former Croatian Serb chief of police, Milan Martić, the Croatian Serbs proclaimed the north-eastern territory of Croatia to be the Republic of Serbian Krajina, RSK. Martić’s attempt to wrest RSK away from Croatia was supported by Slobodan Milošević, now the President of Serbia, and resulted in a policy of ethnic cleansing of Croats and other non-Serbs from Krajina with massive deportations and executions. Martić also ordered the 1995 cluster-bomb rocket attack on Zagreb that deliberately targeted civilian locations. For this, and other war crimes, Martić is now a convicted war criminal and resides in prison – see later.

In 1995, Croatia retaliated with Operation Storm against strategic Croat Serb positions in RSK resulting in defeat for the RSK military forces and, finally, independence for Croatia.

Bosnian War, 1992 – 1995

In 1991, Bosnia and Herzegovina was also seeking independence. At the time, Bosnia was populated by three groups of people – Bosnian Croats (~15%, Roman Catholics), Bosnian Serbs (~30%, Serbian Orthodox Christians), and Bosnian Muslims (~50%, Islam). The Bosnian seat of government in the capital, Sarajevo, was dominated by the Bosnian Muslims, renamed Bosniaks by the Bosniak Assembly in Sarajevo in 1993. Like their Croatian counterparts, the Bosnian government was pushing hard for independence and this raised the ire of the Bosnian Serbs’ political leader, Radovan Karadžić, who threatened bloodshed if the Bosnian Croats and Bosniaks insisted on breaking away from what was now a Serb-dominated ‘Yugoslavia’. Karadžić, with the support of President Slobodan Milošević in Serbia, started a war of genocide and ethnic cleansing against the Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats in Bosnia. Karadžić was backed by the Serbian JNA Army and, more importantly, by the Bosnian Serb Army, an armed force in the self-proclaimed eastern territory of Bosnia renamed Republika Srpska (Republic of Serbia) under the command of General Ratko Mladić.

It’s difficult to select from the many atrocities committed during the Bosnian war but the next sections highlight three events that became ill-famed.

Bosnian War: The Siege of Sarajevo

The Bosnian war took a turn for the worse with the siege of Sarajevo that started in April 1992 and lasted almost four years (officially, 1,425 days) and resulted in somewhere between 10,000 and 14,000 deaths (estimates vary) of the Bosniak and Bosnian Croat defence forces and civilians trapped inside the city. The siege became notorious for a number of reasons: the miserable life-threatening conditions of the inhabitants; the infamous Sniper’s Alley wherein Bosnian Serb snipers had a clear view of the main boulevard in Sarajevo and fired upon anyone trying to cross over; the Holiday Inn hotel where war journalists and reporters stayed; and the fact that this siege lasted so long and was only lifted when, in late 1995, NATO decided to halt the war by bombing Bosnian Serb positions throughout Bosnia and in Serbia.

Bosnian War: Destruction of Stari Most

In 1993-1994, the Bosniaks in Mostar, a Bosnian city close to the western border with Croatia and unofficial capital of Herzegovina, were besieged for ten months by their former allies the Bosnian Croats. The city suffered extensive damage including the destruction of the historic Stari Most, the 16th-century stone-and-mortar Ottoman bridge that linked the two parts of the city across the river Neretva. The bridge has since been reconstructed.

During this particular siege, Bosnian Croat snipers made use of a former bank building on their side of the Neretva river to snipe at Bosniaks across the river. One estimate claims 225 killed, 60 of whom were children, and a further 1,030 wounded.

Bosnian War: Srebrenica Massacre, Dayton Agreement

Throughout the war, the Bosnian Serb army, and others, committed many acts of genocide (systematic killing of a racial or cultural group), ethnic cleansing (mass displacement of a racial or cultural group) and other war crimes (murder, rape, brutality, persecution, etc.). One incident that stands out was the Bosnian Serb massacre of 8,000 Bosniak men and boys from Srebrenica, an eastern Bosnian salt-mining town very close to the Serbian border. The 13th July 1995 massacre was conducted by the Bosnian Serb Army under the direct command of General Ratko Mladić and was instrumental in demonstrating the complete ineffectiveness of the UN peacekeepers stationed in the town. The peacekeepers were neither able to intervene nor prevent the massacre and, ultimately, the Srebrenica massacre, and, a few weeks later, the shelling of civilians in Markale (the market place) in Sarajevo, finally convinced NATO that such crimes against humanity could only be stopped by force. NATO commenced a bombing campaign (Operation Deliberate Force) against the Bosnian Serb army on 30 August 1995, forcing the Bosnian Serbs to cease hostilities and negotiate a UN-sponsored peace settlement in Dayton, Ohio. The Dayton Agreement, also known as the Dayton Peace Accords, was signed in Paris on the 14th December 1995 thus ending the Bosnian War.

The aftermath of the Bosnian War

The aftermath of the Bosnian War

The Dayton Agreement resulted in the creation of a federalised Bosnia divided between a Croat-Bosniak federation named the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH), and the Republika Srpska. The FBiH is what used to be the west and central part of Bosnia and is governed by the Bosniaks (mostly) and Bosnian Croats. Sarajevo on the eastern FBiH border is the capital of FBiH. The Republika Srpska, mostly populated by the Bosnian Serbs, consists of the northern and south-eastern territories separated by a shared FBiH/ Republika Srpska self-governing territory called Brčko District. Banja Luka, the Srpska capital and seat of government, maintains an alliance with the Serbian government in Belgrade but Republika Srpska is not a part of Serbia, nor is it a country in its own right. Like FBiH, Republika Srpska is a geographic region and political entity in federalised Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Kosovo War, 1998 – 1999

Kosovo, the region between Serbia to the north-east and Albania to the south, has had a mixed history. Essentially, the area has been a tug-of-war between Serbia and Albania ever since it was formerly identified as part of Yugoslavia after WW2. Ethnically, the majority of Kosovo’s inhabitants are Muslim Kosovar Albanians but in 1991, the Kosovo government in the capital, Pristina, was dominated by Christian Kosovar Serbs. Throughout the late-‘80s, Milošević increased Serbian control over Kosovo and started a suppression of the Kosovar Albanian culture and religion. This policy resulted in a non-violent separatist Kosovar Albanian movement and, finally, a declaration of independence in 1992 – the Republic of Kosovo. Unfortunately, Kosovar Serbs neither participated in the elections nor recognised the Republic. Similarly, the Dayton Agreement also failed to recognise Kosovo as a separate country and in 1996, the Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA, made up of initially ill-equipped Kosovar Albanians, was formed and began a guerrilla war against the ruling Kosovar Serb government and army.

The war escalated throughout the late-‘90s and came to a head when NATO decided to assist the KLA and in March 1999, commenced bombing raids against the Kosovar Serb strategic and military positions in Mitrovica, the centre of Kosovar Serb operations in northern Kosovo. NATO also bombed the Serbian capital, Belgrade, including, unfortunately, the Chinese Embassy. These raids ended the Kosovo War and with the signing of the Kumanovo Agreement in Kumanovo, Greece, between the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) and a NATO-led international peace-keeping force known as the Kosovo Force, KFOR, governance of Kosovo was placed in the hands of KFOR and there it will remain until the Kosovo Security Force, formed in 2009 from members of KFOR and a Kosovar civilian emergency service known as the Kosovo Protection Corps, KPC, is able to take over. That process is continuing.

Montenegro Independence, 2006

Given that Montenegro aligned itself with Serbia during the 1991-1995 Balkan Wars, forming the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, there was no Montenegro War of Independence. Instead, Montenegrin military personnel were included in the JNA and took part in JNA operations including the siege of Dubrovnik and other offensives in both Croatia and Bosnia.

In 1996, the Montenegrin government in the capital, Podgorica, began to break away from Serbian influence and successive governments started working towards full independence which was finally achieved in 2006.

ICTY war-criminal trials, and the future

Following the 1995 peace agreements, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, ICTY, in The Hague, began war-criminal proceedings against Slobodan Milošević, Radovan Karadžić, Ratko Mladić, Milan Martić and a further 157 alleged war criminals. Karadžić, Mladić and Martić were all found guilty of various crimes against humanity including genocide and ethnic cleansing and are currently serving life sentences in prisons in The Netherlands and Estonia (Martić). Milošević, although charged with the same crimes, died in prison in 2006 before his trial could be brought to conclusion and thus was never found guilty of any crimes. Of the total number of 161 indictees, 94 were Bosnian Serbs or Serbs, the rest were a mix of Croats, Albanians, Bosniaks, Macedonians and Montenegrins. To date (September 2019), 89 indictees, including 62 of the Bosnian Serbs/Serbs, have been convicted of a wide variety of war crimes and are now serving prison sentences.

There is no doubt that, although legally binding, the various peace treaties are seen by some observers as fragile. The genocide and ethnic cleansing actions during the wars has resulted in massive changes to the demographics of the countries that make up the Balkans but particularly in Bosnia where an estimated 200,000 Bosniaks died and a further 2 million displaced. Religious divides still exist and many Bosniaks in FBiH view Republika Srpska as an illegitimate federation created by the illegal actions of genocide and ethnic cleansing: a situation fraught with future unrest. Similarly, over 1 million people (some say, 1.45 million) were displaced during the Kosovo war and not all have returned causing unrest in the adjacent countries of Hungary, Albania, Bulgaria and Romania.

Following Montenegro’s successful bid for independence in 2006, Kosovo, formerly a part of Serbia, followed suit and declared its independence in 2008. This action is still a bone of contention with Serbia. Some countries recognise Kosovo as an independent country; others, notably Serbia and Russia, do not.

But, right now, the Balkan countries are safe to travel to and open for business. Tourism is booming again. We can only hope that the inhabitants of the former Yugoslavia will rise above lines of ethnic and religious divisions and embrace the rich diversity of their cultures and religions, their many attractive cities and towns, and the magnificent beauty of their scenic mountains and coastline. It’s a region that we enjoy visiting immensely and we will continue to travel to all of the countries of former Yugoslavia with passion and without prejudice.

Acknowledgement: We are indebted to the anonymous authors of the many articles on Wikipedia we consulted to create this summary of events surrounding the Balkan Wars in the 1990s. 2,900 words do not do justice to the detail and precision of these authors, nor to the true complexity of the wars.

READ MORE BLOG POSTS ABOUT THE BALKANS

IF YOU FOUND OUR QUICK GUIDE TO THE BALKAN WARS INTERESTING, PLEASE SHARE IT…

Very interesting. We are currently in Croatia and have been reading a lot about the recent history. Thanks for taking the time to write this informative post.

You are welcome and I’m glad you found it informative. I can also recommend The Death of Yugoslavia, a fascinating six-part BBC documentary that was first shown in 1995 and includes interviews with some of the key players such as Milošević and Tuđman. They are all available on Youtube if you want to watch them.

A good and interesting summary of the recent history of these terrible events I will also be viewing the BBC documentary. ank you for taking the time to write this pos.

Thank you for taking the time to respond. It was a tricky post to write/summarise so we appreciate your feedback.