A comprehensive guide to sights in and around Shipka and Kazanlak aside from the Buzludzha monument

Buzludzha, the huge monument completed in 1981 at the behest of the Bulgarian communist government as a meeting hall and to commemorate the first united meeting of the country’s socialist groups, is well and truly locked up these days. The main entrance has been welded shut for some time and you’ve got to have some sympathy for the 24-hour security guard posted nearby, who would continually be blasted by the elements if it wasn’t for the provision of a small century box for protection. Furthermore, since being awarded a $185,000 grant from the Getty Foundation in 2019, work to preserve parts of the structure, including the stabilisation and protection of some of the most vulnerable mosaics, has been taking place. To attempt to enter Buzludzha these days would not only be illegal and foolhardy but would also jeopardise the efforts of those working to preserve the monument.

It is still permitted to view the exterior of this striking symbol of communism and, arguably, this is reason enough to traverse the zigzag route that leads up this remote peak in the heart of the Balkan Mountains.

But, since the time of the 1877-78 Russo-Turkish War, when decisive battles were fought and won in this part of the country, the peak and the region surrounding it has played a significant role in Bulgarian history. During Bulgaria’s communist period (1944-1989), many monuments and memorials were erected to pay homage to the Russo-Turkish War and the key events that followed, thereafter; namely the meeting of the socialists mentioned in the opening paragraph, the failed September Uprising of 1923, and also partisan resistance against fascist forces during World War II. Further explanations about each of these historical events are given in the relevant sections below but, in short, there is more to see in the vicinity of Buzludzha than simply the Memorial House itself. And this includes monuments and memorials, along with some architecture, that do not have a connection to Buzludzha but were also erected/constructed when Bulgaria was a socialist republic.

Our suggestion for an interesting 1-day itinerary in the vicinity of Buzludzha would be:

Kazanlak – Kran – Buzludzha – Shipka Pass – Shipka – Sheynovo – Dunavtsi – Kazanlak

Map showing significant monuments and memorials near Buzludzha

Visiting the places of interest in the vicinity of Buzludzha

You will need your own wheels to cover the ground we are suggesting. Public transport is thin on the ground between the towns and villages mentioned, and there is none at all heading up Buzludzha Peak. Hiring a car is the most flexible option. Other traffic in this part of the country is relatively sparse and the roads are in good condition. If you don’t want to drive yourself, there are travel companies in Sofia, Veliko Tarnovo and Plovdiv that arrange tours to Buzludzha. It is unlikely any of them will offer everything we’ve listed on a fixed tour but arranging a bespoke itinerary should be easy enough. The final option is to arrange a taxi locally to take you around – Kazanlak and Shipka are the best places to do this as they are the nearest settlements to Buzludzha and the drivers will be local and should know the region well.

Before getting down to details, I would like to say that I am grateful to Stefan Spassov, who provided me with several snippets of information about some of the monuments/memorials listed below. Stefan runs @TheForgottenCivilization, an interesting Instagram profile focusing on photos and text related to Bulgaria’s socialist period (1944-1989).

Kazanlak

Kazanlak, along with Shipka (see below), is a good base for visiting Buzludzha and the places of interest surrounding it. Approximately 24kms south of Buzludzha, Kazanlak is an ancient town that is famous throughout Bulgaria for its production of rose oil. Indeed, Kazanlak is situated at the eastern end of the Rose Valley, a large area in the centre of the country that has been cultivating roses for centuries and produces almost half of the world’s rose oil. There is plenty of information online about Kazanlak and its association with the fragrant plant, including details of the annual Rose Festival which takes place in the first week of June, but as this is an article about locations associated with Bulgaria’s socialist past, I’m going to move on and highlight the town’s ‘alternative’ attractions.

Grand Hotel

The first thing we came across whilst walking around Kazanlak was the centrally-located Grand Hotel. Dating back to the early 1980s and also known as the Kazanluk Hotel, the property is situated on the east side of the town’s main square and is a good example of socialist modernist architecture. The hotel was designed by architect Mihail Vitanov.

Monument “Thracian Woman”

Also on the square is the monument known as “Thracian Woman”. Kazanlak’s association with the ancient Greeks became the focus of attention when a 4th century-BCE tomb of a Thracian ruler was discovered nearby in the former Thracian capital of Seuthopolis. The burial chamber, which is ornately decorated with frescoes, was discovered in 1944 during the construction of a bomb shelter and was awarded UNESCO World Heritage status in 1979. The statue of a Thracian woman in the park was erected in the late 1980s, presumably as a recognition of this fact. The sculptor was Doko Dokov

Historical Museum ISKRA and House Of Culture Arsenal

We also found two other examples of interesting modernist architecture in Kazanlak. The first of these was the Historical Museum ISKRA and the second was the House Of Culture Arsenal. The museum dates from 1981 whereas the House of Culture Arsenal wasn’t completed until 1992 even though work on its construction started in 1976. The reason for the delayed completion was down to continued developments and improvements in the overall design of the structure for which there weren’t funds due to the turbulent economic crisis that took place in Bulgaria during the late 1980s. Details of the architects who worked on each project can be found here and here.

Krân

Leaving Kazanlak and heading north on the road to Shipka, the first place of interest en route to Buzludzha is the village of Krân.

Monument to the 1923 September Uprising

Before reaching the settlement-proper, there is a Monument to the 1923 September Uprising near the petrol station on the left-hand side of the road. As I explain in this post about socialist-era monuments and memorials in Bulgaria, the 1923 September Uprising was a failed military insurgency in which the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP) attempted to overthrow the country’s government at the time, the recently appointed Democratic Alliance which was headed by the Bulgarian interwar politician, Aleksandar Tsankov. After the revolt’s failure, those involved were vilified by the powers-that-be. But, when the BCP eventually took over the running of the country in 1946, those same people were elevated to the status of heroes of anti-fascism and many monuments and memorials were erected throughout Bulgaria, and particularly in the central part of the country where some of the key events took place, to commemorate them and the occasion itself.

The Monument to the 1923 September Uprising on the edge of Krân was erected in 1973 in honour of the 50th anniversary of the revolt. The sculptor was Dimitar Kopchev.

Monument to the Bulgarian Communist Party

Entering the village, there are two more monuments in the central park associated with the 1923 September Uprising. The first is the Monument to the Bulgarian Communist Party, which was also completed in 1973. The Inscription reads “Here was the club-building of the local BKP (Bulgarian Communist Party) in which in the evening of 19-20 September was created the headquarters of the rebellions in the village of Krân.”

Monument to General-Major Tsvyatko Radoynov

The other statue in Krân is the Monument to General-Major Tsvyatko Radoynov. Radoynov was a political and military figure in the Bulgarian Communist Party who participated in the 1923 September Uprising in Burgas, a city on the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast. Like other important figures in the uprising, including Georgi Dimitrov who went on to become the first communist leader of Bulgaria, Radoynov fled the country after the defeat. He ended up, by way of Turkey, in the Soviet Union and reached the rank of colonel in the Red Army. During World War II, he returned to Bulgaria illegally to support the communist resistance (*), where he was informed upon, captured, put on trial and ultimately executed by firing squad in 1942.

(*) Bulgaria was allied with the Axis Powers during the war and fought on the side of the Germans.

The event became known as the “parachutists and submariners” because some of the Soviet-backed sabotage units, there were nine in total, were parachuted in while others, including Radoynov’s, swam ashore from submarines that surfaced off the Black Sea Coast, near the mouth of the Kamchia River.

Radoynov was born in Krân in 1895 and an interesting fact about the monument to him is that it was the work of Dimitâr Ostoich, a Bulgarian sculptor who was married to Radoynov’s daughter. She, in turn, was named Septemvrina in honour of the 1923 September Uprising. The Monument to General Major Tsvyatko Radoyno was erected in 1985.

Monument to Dimitar Blagoev

At the junction where the Kazanlak-Shipka road splits and makes its way up Buzludzha Peak is a 6-metre tall, metal statue of Dimitâr Blagoev, a philosopher and founding member of the Bulgarian Social Democratic Workers’ Party. In 1891, it was Blagoev who arranged the first gathering of the various socialist groups within Bulgaria. His intention (and hope) was to unite the various fringe movements into one political party. The discrete meeting, which was held on 2nd August and later became known as the Bulgarian Socialist Congress, took place in the beech forest on the southern slope of Buzludzha Peak and is the reason why the Buzludzha Monument seen today is located where it is. Erected in 1981, this monument marks the 100th anniversary of the meeting.

Buzludzha Peak

The majority of visitors are in a hurry to reach the Buzludzha Monument and if it is your first time seeing the fantastical structure then I wouldn’t blame you. But, it is worth stopping either on the way up (or the way down if impatience gets the better of you) to see the other monuments in the vicinity of the star attraction. Apart from the Monument to the Road Brigade and the Monument to the Two Generations Shipka-Buzludzha, all of the memorials are clustered in the forest where the Bulgarian Socialist Congress was held.

Monument to the Road Brigade

This monument, which is partway up Buzludzha Peak, is in recognition of the Regional Youth Brigade Georgi Dimitrov, the organisation assigned to construct the road leading to the top. The sculptor was Todor Todorov.

Monument to the Fatherland Front

Entering the area on the southern slope of Buzludzha Peak where the Bulgarian Socialist Congress took place, the first of the ensemble of monuments located here features an OF/ОФ symbol, along with the hammer and sickle. OF/ОФ is an abbreviation for the Otechestven Front, which translates as the Fatherland Front, the Bulgarian partisan/resistance movement during World War II. The lion features in the country’s coat of arms and is a symbol of Bulgarian statehood. Completed in 1988, the monument was sculpted by Stoyu Todorov.

Monument to the Buzludzha Congress

Unveiled 70 years after the event (1961), this moss-covered bas-relief honours the historic first meeting of the Bulgarian Socialist Congress instigated by Dimitâr Blagoev. The architectural team who created the piece of work comprised of Kalin Boyadzhiev and Boris Nenkov (architects), and Dimitâr Daskalov, Georgi Gergov and Ivan Kesyakov (sculptors).

Monument to Hadzhi Dimitar

Hadzhi Dimitar (1840-1868) was a legendary revolutionary and voivode (a Slavic title for a military leader) who fought continuously for the freeing of Bulgaria from Ottoman rule. In the last year of his life, he banded forces with Stefan Karadzha, another prominent Bulgarian revolutionary opposed to Ottoman occupation. Established in Romania, the detachment crossed the Danube and engaged in a series of battle with soldiers and bashi-bazouk (irregulars) from the Turkish army before reaching Buzludzha Peak. Karadzha was wounded and captured during one of the skirmishes and the remaining 58 fighters proceeded to Buzludzha Peak under the command of Dimitar. The battle at Buzludzha took place on 30th July 1868 and the heavily-outnumbered group of revolutionaries were defeated by the Turks. Dimitar was injured during the conflict and although he was taken to safety, he succumbed to his wounds and died just over a month later on 10th August 1868.

Officially, Buzludzha is named Hadzhi Dimitar Peak in his honour, although it is rarely called by this title. The monument was erected in 1961 and is the work of Lyuben Dimitrov (sculptor) and Zvetan Zvetkov (architect).

Monument to the Fallen Partisans

Also known as the Monument to the Three Killed Guerrillas of the Gabrovo-Sevlievo Detachment, this memorial was also unveiled in 1961. Part of the partisan movement in Bulgaria during World War II, this underground guerrilla unit carried out numerous acts of sabotage against the fascist forces during the course of the war. This included an ambush attack on Buzludzha Peak towards the end of January 1944 in which three of the partisans were killed by the enemy. The monument is the work of Ivan Tatarov (architect), and Stella Raynova and Ivan Ivanov (sculptors).

Monument to the Two Generations Shipka-Buzludzha

The final location of interest en route to the top of the peak is the Monument to the Two Generations Shipka-Buzludzha. Situated southwest of the Buzludzha Monument, and providing a fantastic view back up towards it, this powerful sculpture comprises two fists clutching flaming torches. It was completed at the same time as the Buzludzha Monument (1981) and represents the passion (fire) of the national liberation movement and the passing of the flame of socialism from one generation to the next. The monument is the work of sculptor, Stoyo Todorov.

Shipka Pass

Freedom Monument on Shipka Pass

The Shipka Pass is about 6kms west of Buzludzha as the crow flies. The scenic pass cuts through the Balkan mountain range which divides the country into north and south. As well as offering splendid views, the pass is known as the scene of some of the most important conflicts of the 1877-78 Russo-Turkish War, which was fought between the Ottoman Empire and the Russians, who were aided by Bulgarian voluntary army units. The four consecutive battles, which took place between July 1877 and January 1878, were collectively known as the Battle of Shipka Pass and the end result was a defensive victory for the Russian/Bulgarian forces and the continued control of a key supply line through the mountains. The Bulgarian volunteers, who numbered approximately 7,500, played a decisive role in the second and fourth battles at Shipka Pass.

The Freedom Monument was unveiled in 1934 in honour of the events that took place in this remote part of the country. The 31.5-metre stone tower, which includes a marble sarcophagus housing the remains of some of the Russian and Bulgarian soldiers who fought in the battles, was the work of Atanas Donkov (architect) and Aleksandar Andreev (sculptor).

A shortcut road, which is in excellent condition, leads from the Monument to the Two Generations Shipka-Buzludzha directly across to the Shipka Pass, meaning it is not necessary to go back down Buzludzha Peak to connect the two locations.

Shipka

Shipka is a sleepy town with not much going on but it’s another good base for exploring Buzludzha and around. Most visitors come here to see the lovely Shipka Monastery, known locally as the Russian Church. Its golden onion-shaped domes are like a miniature version of the grand Orthodox churches in Russia and Ukraine. But, there are a handful of monuments erected during the country’s communist era also in Shipka that are worth searching out if passing through.

Monument to the 1923 September Uprising

Shipka’s Monument to the 1923 September Uprising is in the centre of the town and I’m assuming, like the one near Kran, it was erected in 1973 to mark the 50th anniversary of the rebellion.

Additional monuments in Shipka

There are two more socialist-era monuments in Shipka itself and a further stone monument featuring bas-relief on the roadside, about 2km south. The monument in the lefthand photo represents two haiduti, or hajduci as it is also spelt. Existing in parts of central and southeastern Europe from the early 17th to mid 19th centuries, a hajduk was a cross between a bandit, a mercenary and a freedom fighter. In Bulgaria, and other parts of the Balkans under Turkish rule at the time, they predominantly targeted representatives of the Ottoman Empire, either for plunder or as guerrilla fighters opposed to Turkish rule. In Balkan folklore, they were sometimes romanticised as hero-figures and somewhat comparable to Robin Hood and his band of merry men. Both this monument and the one in the centre of the three images below were created by sculptor Hristo Pesev.

As for the roadside monument 2kms from town, I can shed no light on what it symbolises.

Sheynovo and Dunavtsi

If you are using Kazanlak as a base for exploring the area, or are heading back that way, it’s possible to take an alternative road via the villages of Sheynovo and Dunavtsi if you don’t mind a little bit of extra driving.

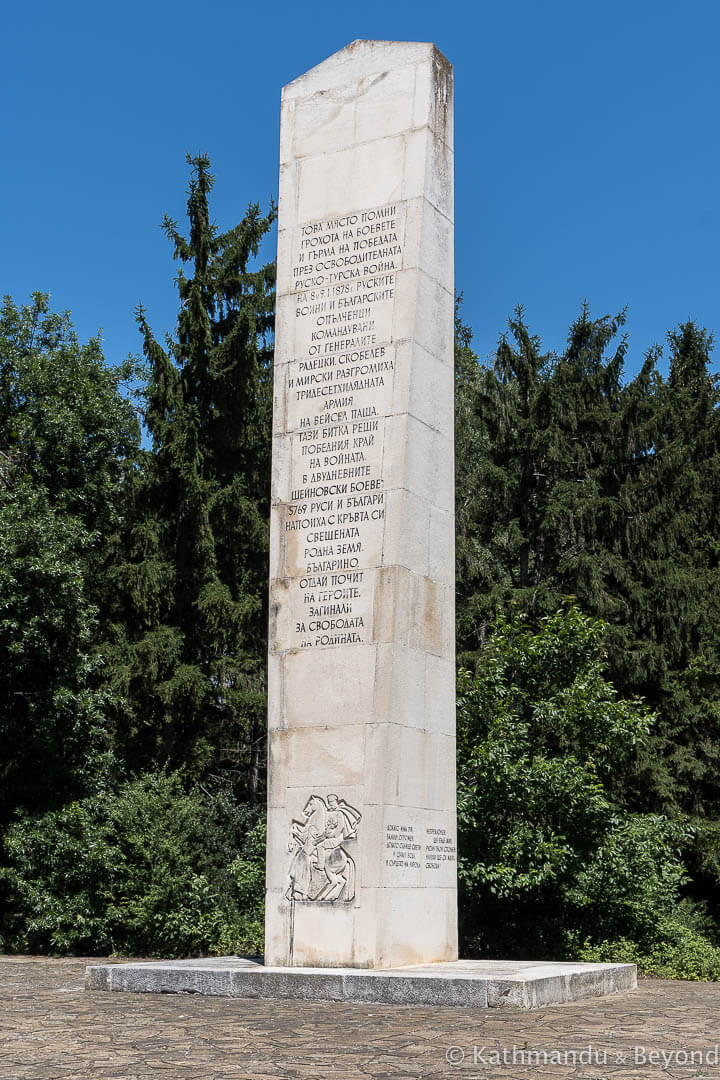

Sheynovo welcome sign and Monument to the Russo-Turkish War of 1878

In Sheynovo we spotted a welcome sign/town marker on the edge of town as well as a large obelisk/monument dedicated to the Russo-Turkish War of 1878. The Battle of Sheynovo, which took place on the 27th and 28th of December 1878, was a significant victory for Russian and Bulgarian forces during the 1877-78 Russo-Turkish War. Not only did it result in the capture of the entire Central Ottoman Army (3 pashas, 765 officers and 22,000 soldiers), it also opened up the way for an offensive into Turkey itself by way of Thrace and the historical city of Edirne. The anniversary of the battle is marked with a gathering at the Monument to Victory, as it is also known, each year in early January. The monument was unveiled in 1968 and created by sculptor, Stela Raynova.

“Dunavtsi” Monument and Dunavtsi Municipality

Dunavtsi is even smaller than Sheynovo. Located about 10kms northwest of Kazanlak, in the main square there is a monument, which I believe is called “Dunavtsi” and represents two rivers flowing into one. The reason I am a little hesitant is that I am working from a translation of a Bulgarian Wikipedia page and sometimes information gets lost in translation. As I understand it, Dunavtsi is Дунавци in Bulgarian and it translates as Danube or Danubians and the reason why a village that is at least 100kms south of the mighty river has been named thus is down to a story connected with the fall of the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria’s subsequent independence. To quote from the Wikipedia article;

“After the liberation, the village of Dunavtsi had broken and muddy streets. At that time, the village was called Baslii, after the Turkish ruler of the time – Bey Bayasal. There was a wedding in the village. As they walked along the rain-soaked streets, the wedding guests got dirty and the godfather, who was from Northern Bulgaria, exclaimed with extreme indignation: “Hasn’t this village been flooded by the Danube River, that it’s so muddy ?!”. Since then, the local population has adopted the name Dunavtsi as the name of the village.”

Out of interest, there is another town of the same name in northwestern Bulgaria that is situated on the banks of the Danube. The northern Dunavtsi was established in 1955 by merging the two villages of Vidbol and Gurkovo.

Assuming we identified the correct monument (it is supposed to be in the centre of the village, which this one is) then just behind it is the municipality on which there is some decorative relief on the outer wall.

IF YOU ENJOYED OUR GUIDE TO MONUMENTS AND MEMORIALS NEAR BUZLUDZHA PLEASE CONSIDER SHARING IT…

Hello Mark

While researching places to explore in Bulgaria, I found this blog post. While I haven’t had the chance to journey to Bulgaria just yet, your article has sparked a strong desire to discover these historical sites.

Best regards, Nicholas

Hi Nicholas,

That is nice to hear; thank you! Enjoy your time in Bulgaria when you decide to visit! The central part of the country is fascinating and the countryside is also superb!

Regards, Mark

I did a road trip around Bulgaria back in 2015, but never got around to labelling most of my photos. SO your blog was extremely useful in finding out what and where my photos were of 🙂

Hi Antony, I am pleased to hear that our post was useful in helping you label your photos. If you are missing anything, there is a great website called Witness of Stone, which catalogues many more socialist-era monuments in Bulgaria.

https://witnessesofstone.com/