Discovering Phnom Penh’s Architectural Heritage from French Colonial buildings to New Khmer Architecture

Another aspect of our return visits to Phnom Penh is that it is impossible to not notice the alarming rate at which the city is developing structurally. New, nondescript buildings are going up everywhere you look and it is apparent that not everyone involved in the reconstruction of the city is sympathetic to its earlier architecture and the heritage attached to it. Hence, some of the buildings listed below no longer exist or are on the verge of being demolished in the name of progress. For the sake of posterity, I have kept these buildings in the post but added a note to say they are no more.

Finally, we have also upgraded the article by adding a map pinpointing the locations of the French Colonial and New Khmer architecture featured.

You don’t have to wander very far from the busy tree-lined riverfront to realise what a fascinating city Phnom Penh is, architecturally. Just a few block behind the Royal Palace and the National Museum of Cambodia, two of the capital’s most prominent landmarks, French colonial-era buildings from the 19th and early-to-mid 20th century rub shoulders with structures that fall into a genre of architecture known as New Khmer Architecture, a phrase coined to describe the wave of architectural flourish that combined Khmer tradition with Modernism in the 1950s and ’60s.

We are certainly fans of French colonial architecture and are always happy to come across characteristic structures from that era whenever we are in the region that once formed French Indochina, namely Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos. Indeed, there is a sizeable amount of the genre featured in this article but it was the distinctive look of the New Khmer Architecture that we ended up seeing that, ultimately, grabbed the lion share of our attention during our more recent visits to the Cambodian capital.

The 1950s and ‘60s were a golden period for Cambodia. The Kingdom had gained its independence from the French (1953) and the then king/prime minister, Norodom Sihanouk, had an all-encompassing vision of creating a new, modern and progressive Cambodia that would be a key player on the world stage. This post-independence project was probably a tad overambitious but part of his plan involved the development of the country’s own unique style of architecture. A new generation of Cambodian architects, many of whom, not surprisingly, had studied in France, worked on the project over the following years but the foremost architect who would emerge as the driving force behind the New Khmer Architecture movement was a man called Vann Molyvann, a gifted designer who was a favourite of Norodom Sihanouk. Vann Molyvann passed away on 28th September 2017, aged 90. His legacy includes the Chaktomuk Conference Hall, the Independence Monument and the Olympic Stadium which, when completed in 1962, was the most coveted arena in all of Southeast Asia. His work features heavily in the rest of this post.

Among the various styles of architecture in Phnom Penh, you can see distinct brutalist design-influences in some New Khmer Architecture, which is not surprising given the movements emerged around the same time as one another. It is also apparent in some examples of the style that the French influence was still very much in the back of the architect’s mind when creating the original blueprint. There were also strong elements of traditional Khmer architecture incorporated into some of the designs, of which the Independence Monument and the Chaktomuk Conference Hall are good examples.

New Khmer Architecture came to an abrupt end in 1970 when a US-backed coup lead by Cambodian military general, Lon Nol, ousted Norodom Sihanouk from power. Incredibly, many buildings of note in Phnom Penh survived the turmoil and devastation that followed (which included the brutal reign of the Khmer Rouge (1975-1979)), although some were destroyed during that time and many of those that remain today are visibly in poor shape.

Taking both the past and future into consideration, the prospect for Phnom Penh’s architectural heritage, both New Khmer Architecture and before, is not a good one. But, while it is still standing, the distinctive architecture showcased below is one of the overriding reasons why we consider the city to be one of the most captivating in all of Southeast Asia.

Locating Phnom Penh’s French Colonial and New Khmer Architecture

Everything listed below is marked on the map. Assuming you have a central base within the city, i.e. not too far from the riverside promenade, most places mentioned can be incorporated into a walking tour which shouldn’t take more than a full day to complete. The notable exceptions are the Olympic Stadium and the Royal Phnom Penh University/Institute of Foreign Languages. The stadium is just about walkable from the downtown area but it’s a horrible route with lots of traffic and not a lot of pavement. It’s more convenient to take a remork (Cambodian-style tuk-tuk) and you will definitely have to take some form of transport to reach the university, which is about 4.5kms to the west of everything else.

If you don’t want to take a self-guided Phnom Penh architecture tour, or you want to learn more about what you are seeing we would suggest a company called Khmer Architecture Tours. They offer guided group and bespoke walking and cyclo tours of the city’s modern and colonial architecture for very reasonable prices. Guides tend to be a mixture of students of architecture, researchers as well as local and expat architecture enthusiasts. We haven’t been on one of the tours ourselves because the timing didn’t quite work out for us but we know people who have and they come highly recommended.

Map showing the most distinctive architecture in Phnom Penh including New Khmer Architecture and French Colonial buildings

French Colonial and New Khmer Architecture in Phnom Penh

Chaktomuk Conference Hall

Located on the waterfront, this large conference hall held its first venue in 1961 when it hosted the sixth meeting of the World Fellowship of Buddhists. The fan-shaped/palm leaf design is inspired by traditional Angkorian architecture and the building is considered to be one of Vann Molyvann’s most iconic structures. It was originally known as La Salle de Conference Chaktomuk and was abandoned during the time of the Khmer Rouge but is in use once more. The auditorium underwent a complete remodelling in 2000 to bring the facilities up to international standards but the facade of the building remained unchanged.

Hotel Cambodiana

With a prime position overlooking the river, the Hotel Cambodiana was constructed in New Khmer architectural style. The hotel was built on the instruction of Norodom Sihanouk and the architect, Lu Ban Hap, was another of his favourites. Lu Ban Hap was also partly responsible for the city’s now-demolished White Building (see below) as well as Villa Romonea, one of the most iconic modernist villas in the Cambodian seaside town of Kep.

Built on reclaimed land, Norodom Sihanouk originally wanted the property to consist of ten luxury bungalows which he would use to accommodate state visitors and his close associates. But, Lu Ban Hap convinced him to build a much larger hotel that would be up to international standards and the first of its kind in the kingdom. Work on the complex started in 1963 and was finished in 1969. This was just one year before Lon Nol’s overthrow of Norodom Sihanouk and soon after the coup, the property was turned in to military barracks. The place became abandoned during the period of the Khmer Rouge and served as housing for refugees after the despot regime had been forced to flee back to the countryside.

It wasn’t until the late 1980s that a Singapore-based company took on the lease of the property. They renovated and expanded the hotel and it eventually reopened in July 1990. During the period when the United Nations peacekeeping operation, UNTAC (United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia), were in the country (March 1992 – September 1993), practically all visiting diplomats and journalists stayed at the Hotel Cambodiana.

According to this article in The Phnom Penh Post (dated February 2018), there are plans afoot to demolish the Hotel Cambodiana and replace it with a skyscraper that ‘could reach over half a kilometre into the sky’ …

Capitol Cinema

Norodom Sihanouk was a huge fan of cinematography and produced more than fifty films throughout his lifetime. As a result, there are several cinemas in Phnom Penh dating back to the 1960s and beyond. The original structure of this cinema dates back to 1955 but it was renovated by Vann Molyvann in 1964, which is when the jagged roof, a characteristic of his design, was added. The Capitol Cinema is no longer used for anything.

Former US Embassy

This building was home to the American Embassy until 1965 when diplomatic relations between the two countries broke off for the first time. The second and only other time to date that diplomatic ties were broken was in 1975, just before the Khmer Rouge came to power. The building now houses apartments and isn’t in particularly good condition.

Ministry of Industry, Science, Technology & Innovation

This building is directly opposite the former US Embassy and was originally used by the Americans as an operations building in the 1960s.

Public toilet

This public toilet is one of a pair situated at opposite corners of the open space in front of the National Museum. They were constructed in 1959 in modernist style and were functional up until the time of their demolition (see below).

Update: Both toilets were demolished at some point in 2016/2017 as part of the redevelopment of Veal Preah Man, the former funerary complex of King Norodom Sihanouk.

National Museum of Cambodia

The National Museum of Cambodia was constructed between 1917 and 1924 and was originally designed by the French architect, historian, archaeologist and all-round champion of Khmer art, George Groslier. The obvious elements of traditional Angkorian architecture incorporated into the museum’s facade make it a possible prototype and inspiration for the New Khmer Architecture movement a few decades later. In fact, the central section of the complex was renovated in 1968 under the supervision of Vann Molyvann – craftsmanship that was discovered in a state of terrible disrepair after the Khmer Rouge had left Phnom Penh in 1979.

Architecture aside, it is definitely worth paying the entrance fee to go inside the National Museum of Cambodia (currently US$10 for adults). The museum has a vast collection of cultural relics from the Angkorian period and is an excellent introduction to the temples themselves.

Former Royal Villa

This lovely French-era structure no longer exists as seen in the photo but at least the two-storey historical property hasn’t been demolished. The building, and the land on which it stands, now belongs to Hyatt Hotels and they have incorporated the distinctive yellow facade into the design of, what will be the Hyatt Regency Phnom Penh. The 247-room hotel was due to open in mid-2020 but on their website, Hyatt state that the property is ‘Opening Soon’ so the project has been delayed. When it does eventually open, it will be the first Hyatt-branded property in Cambodia. There are some interesting photos on the web showing how the villa was protected during construction and merged into the overall design.

The villa itself dates back to the early 1900s and was one of the last remaining mansions associated with the Royal Palace, which is close by. It was used as an office before being acquired by the Hyatt Group.

Post Office

Phnom Penh’s colonial post office was designed by French architect and urban planner, Daniel Fabré, in 1895. It sits on what used to be known as ‘Place de la Post’ (Post Office Square), a central plaza by the river that was once part of the French/European administrative district of the city. The building is considered a good example of neo-classical architecture, although there was criticism that Fabré made no adjustments to the design to take into account the tropical climate, with air circulation no doubt being the biggest gripe.

Former Grand Hotel Manolis

More or less opposite the Post Office, this former hotel was commissioned by Albert Louis Huyn de Vernéville, the French protectorate (i.e. top dog) of Cambodia from 1889 to 1894, as a hotel-restaurant of European excellence. A resident foreign merchant was given the contract to complete the task and in return for a financial subsidy, the protectorate was provided with the exclusive use of several of the rooms at the hotel which would be used to host guests of the French regime. In 1918, the hotel was acquired by a Greek by the name of Manolis and that is how it got its name.

André Malraux (1901-1976), the celebrated French author, art critic, tomb raider and, later, France’s Minister of Cultural Affairs spent a lengthy period at the Grand Hotel Manolis in 1923 while awaiting his fate after being arrested for looting the temple of Banteay Srei at Angkor. He was found guilty but managed to evade prison. As a result of the experience, he ended up becoming a highly critical agitator of the French colonial administration in Indochina and helped publish a nationalist newspaper in neighbouring Vietnam for a period thereafter. More details about Malraux’s colourful life and his achievements can be found here.

The part of the hotel in the photo is actually an extension that was added at some point after 1910. The main building was constructed between 1895 and 1896 and faced the river. From what I can gather, elements of the structure still exist but a rather dominant KFC on the ground floor detracts somewhat from what’s left of the building’s original facade. The extension was converted into apartments at some point in the late 1980s/early ’90s.

Former Central Police Station

This building, which was initially constructed in 1892 and then remodelled in the late 1920s/early ’30s, is also on Post Office Square and was used as the city headquarters of the French colonial police force. It began life as a single storey, rather unassuming structure but during the revamp two more floors were added as well as a series of Art Deco features that made it more distinguishable. Unfortunately, hardly any of these features are still in situ and the building is, overall, in very poor condition. Its fate is in the balance somewhat, and at least since 2016, a corrugated fence encompasses part of the compound. I don’t think anyone lives in it but the courtyard at the back of this horseshoe-shaped building still sees some activity from local residents.

I am assuming that the reasons André Malraux put himself up at the Grand Hotel Manolis while waiting to see what was going to happen to him is because it was convenient for the police station which, presumably, he had to visit frequently?

Independence Monument

The Independence Monument was designed by Vann Molyvann in 1958 and commissioned to commemorate independence from France a few years earlier (1953). Located at the junction of Norodom Boulevard and Sihanouk Boulevard, two of the city’s major thoroughfares, the 37-metre tall monument is one of Phnom Penh’s most recognisable landmarks as well as, these days, one of its busiest roundabouts!

There are no prizes for working out that the design is modelled on the central tower of Angkor Wat.

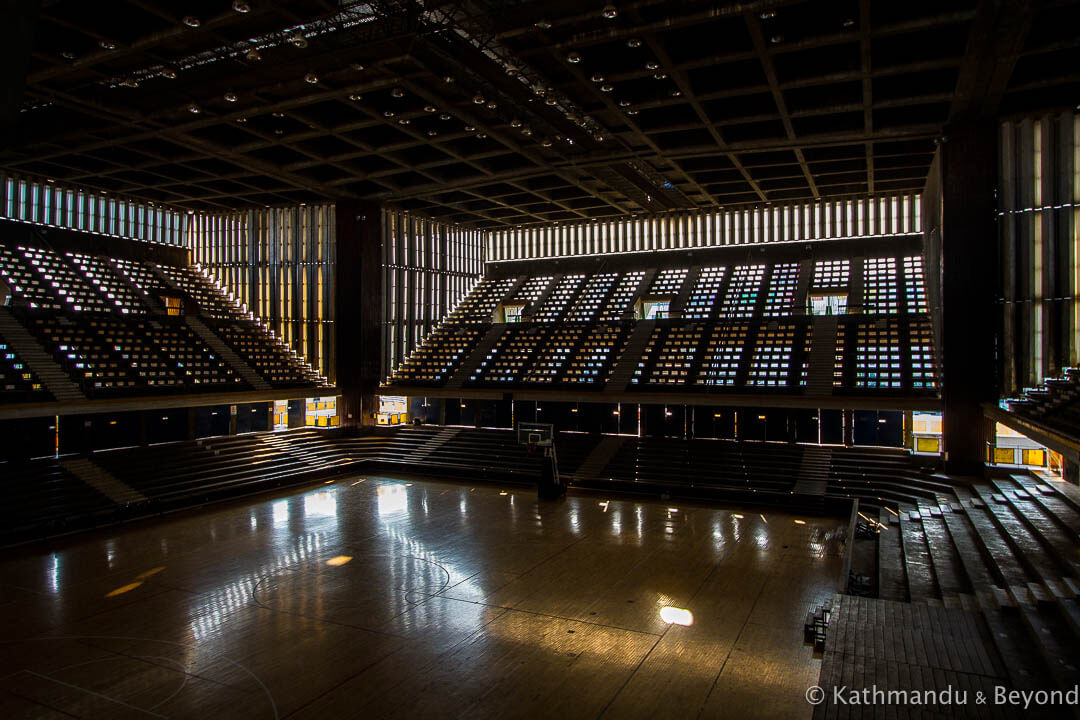

Olympic Stadium

Also known as the National Sports Complex, this Vann Molyvann designed structure is still used for sporting events both at local and international level. Completed in 1964, the stadium was used a year later to host two qualifying matches for the 1966 FIFA World Cup, the finals of which were played in England. The matches were between North Korea and Australia. The North Koreans didn’t have a FIFA-standard venue while Australian immigration laws prevented the Koreans from travelling there. Norodom Sihanouk, who was on friendly terms with the then North Korean leader, Kim Il-sung, stepped in and told FIFA the games could be played at the city’s brand-new stadium. The matches attracted 60,000 and 40,000 fans respectively, and the Cambodian king decreed that half of the spectators would cheer for the North Koreans while the other half would be in the Australian camp! North Korea won both games (quite convincingly) and then went on to reach the quarter-finals of the actual World Cup, although we all know who won it, right?!

On a darker note, during the reign of the Khmer Rouge, the stadium was used as an execution ground and, thereafter, fell into a state of disrepair. It wasn’t until 2000 that the stadium was given a new lease of life. However, the land around the arena is prime real estate and the Taiwanese company which redeveloped the complex also encircled it with rather menacing-looking condominiums and other high-rise developments that conveys the feeling that the stadium is continuously under threat from demolition.

Whether the arena can stand up to the developers, moneymen, politicians and out-and-out heathens who don’t appreciate its architectural importance is a question that is in the balance. All I’ll say is that every time we visit the Olympic Stadium, which is each occasion we return to Phnom Penh (last visit February 2018), the amount of soaring cranes and half-finished construction projects in the immediate vicinity becomes more and more apparent and, although it pains me to say this, I think this magnificent structure is already on borrowed time.

Royal Railway Station

Originally constructed in 1932 during French times, the station was built to service the railway to Battambang in the northwest of the country (*).

(*) Battambang’s 1950s modernist-style station is also worth seeing if you are visiting the city.

I remember the station from my first visit to Cambodia in 1992 when I took a very slow, and quite eventful, train journey from Phnom Penh up to Battambang. Back then, like so many buildings in the city, the station was in a terrible condition having been neglected during the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge. The building seen today is the result of a 2010 renovation project and, as of April 2016, the station is officially open once more with limited passenger services running south to Sihanoukville via Kampot and north to Poipet via Battambang.

As usual in Cambodia, that’s not the end of the story. According to this 2019 article in the Khmer Times, a group of US and European investors plan to spend US$5 million turning the station into an upmarket shopping mall.

Psar Thmei (Central Market)

The Psar Thmei is one of Phnom Penh’s main Art Deco landmarks. It was designed in 1937 by Jean Desbois, a Frenchman who was the architect of the city between 1931 and 1937. The supervision of the construction work was carried out by another French architect, Louis Chauchon. At the time of its completion, it was said to be the biggest market in Asia. Its large central dome was designed to allow maximum ventilation and has four diagonal limbs extending from it. The fact that it was originally constructed on marshland means that flooding during the wet season in the vicinity of the market has remained a problem to this day.

White Building (Municipal Apartments)

The White Building was one of the largest apartment blocks to be established as part of Norodom Sihanouk’s vision for a new Cambodia. What you see in the photo is just one block out of six and in fact, the whole area sprawls for quite some way along the street. The White Building was jointly designed by two architects, a Khmer (Lu Ban Hap) and French-Russian (Vladimir Bodiansky), and the project was overseen by Vann Molyvann. The structure was built in 1963 to house moderate-income tenants and in particular artists and their families, but many either fled during the time of the Khmer Rouge or were forced into the countryside as part of the regime’s ideology of a peasant utopia and the building never returned to its former glory. All six blocks are still in use and house an estimated 2,500 tenants but most of them are poverty-stricken and the housing project has a reputation (which is not necessarily justified) for prostitution, drug use and other such vices.

Update: The White Building was demolished in the summer of 2017.

Cinema Lux

Dating back to 1938, the Lux Cinema was designed in Art Deco style by French architect, Roger Colne. With a 650-seats auditorium, the Lux was one of Phnom Penh’s first glitzy venues and is the only original cinema in the city to have survived closure, demolition or being turned into a restaurant or karaoke bar. These days, it mostly shows low budget Khmer flicks and horror movies imported from Thailand and Hong Kong, although it is still equipped to run 35 mm film, which it does do from time to time. Some say that the movie-theatre is haunted by a cinema-goer who couldn’t handle one of the scary movies and died of a heart attack during the performance.

Update: Cinema Lux stopped functioning as a cinema in the spring 2017 and as of 2019 (see the comment section below), the building itself has been undergoing a slow demolition and is unlikely to be around for much longer.

Raffles Hotel Le Royal

First opened in 1929 simply as ‘Le Royal’, the hotel was designed by French architect and urban planner, Ernest Hébrard who is best known for creating the blueprint for the northern Greek city of Thessaloniki after it was all but destroyed by a Great Fire in 1917.

During its heyday, this grande dame hosted guests such as Charlie Chaplin, Charles de Gaulle and the English novelist and playwright, Somerset Maugham. And, during the early period of the Khmer Rouge, before things got too bad and all foreigners were forced to leave the country, the hotel was used as a base by several overseas journalists including Sydney Schanberg who was one of two main characters, the other being Cambodian journalist Dith Pran, in the 1984 movie, The Killing Fields. The hotel was used as a storage facility during parts of the civil war, as well as after it, and only reverted to becoming a hotel in 1980 when it was named the Hotel Samakki. The luxury hotel chain, Raffles, took on the lease in 1996 and after meticulous renovations reopened the property at the end of 1997 (*).

(*) Raffles simultaneously did the same thing with the historic Grand Hotel D’Angkor in Siem Reap, which I stayed in for a couple of nights during my time in Cambodia in 1992 for the princely sum of US$20 per room per night!

Closing in on its centennial year, the Hotel Le Royal is back at the top of its game and Phnom Penh’s premier luxury hotel once more. If you can’t, or don’t want to spend several hundred dollars in order to stay at the property, consider signing up for the nighttime scooter tour run by Vespa Adventures. This brilliant, and fun-packed excursion takes you around the city on the back of scooters and samples a handful of Phnom Penh’s bars and dining venues in the process. This includes a stop at Le Royal’s renowned Elephant Bar where you will be presented with the bar’s signature Femme Fatale cocktail which was invented for Jacqueline Kennedy when she was a guest at the hotel in 1967.

The Mansion

The Mansion is a ramshackle French colonial-era building directly behind the well-known Foreign Correspondents’ Club (FCC). The landmark building, which dates back to 1917, was a private home for nigh on sixty years, and during the ’60s, the owners had a reputation for hosting lavish parties. The property was abandoned around the time that the Khmer Rouge seized power in the city (17th April 1975) and was subsequently looted of anything of value. When the Vietnamese took Phnom Penh in early January 1979 (part of the Cambodian-Vietnamese War, which lasted from 15 December 1978 until 26 September 1989), they occupied the once-opulent mansion and used it as a billet/command centre until they left a little over a decade later.

After a spell as a police station, the building was acquired by the FCC in 2009. They use as an outdoor bar and a place to host cultural events but, according to their website, they are planning to convert at least part of it into four luxury suites as part of a major renovation project which includes upgrading the Correspondents’ Club as well. The work was due to be completed in mid-2021.

Kandal Market

Kandal Market, which is centrally located just one block back from the riverfront, is one of the oldest markets in the city. The modernist-style building seen in the photo, however, is a relatively recent addition and the fact that the year “1990”, along with the name of the market in Khmer, is etched into the concrete above the main entrance would suggest that the building itself dates from that time.

The Royal University of Phnom Penh

Constructed in the late 1960s, the Royal University of Phnom Penh is, not surprisingly, the largest academic institution in the country. The university was designed by French architects, Leroy and Mondet, and the most interesting part of the campus is the large Auditorium Hall, which can be seen on the right as you enter the complex. The parabolic structure was created to allow maximum air circulation and for large amounts of light to stream in but, apparently, this style of building is terrible for acoustics, which is a bit of a design flaw for an assembly room.

Another interesting piece of Phnom Penh architecture, which looks like it should have been constructed in the 1960s or ’70s but, in fact, only dates back to the early to mid-1990s, is the Hun Sen Library building which you will find just to the left of the main section of the university when facing it. It was designed by another of Cambodia’s veteran architects, Mam Sophana, who fled the country for Singapore in 1974, a year before the Khmer Rouge took power. He didn’t return to Cambodia until 1992 and during his time in Singapore, his most important achievement was his involvement in the design and construction of Changi International Airport, which opened in July 1981.

The university, along with all other educational institutions in Cambodia, was closed down during the period of the Khmer Rouge and many teachers and students from the institution, including the faculty’s dean, Phung Ton, were systematically arrested and taken to the notorious Tuol Sleng (S-21) prison on the other side of the city, where they were tortured and then murdered before, doubtless, being deposed of at the ‘Killing Fields’ at Choeung Ek. The university reopened in 1980.

Institute of Foreign Languages

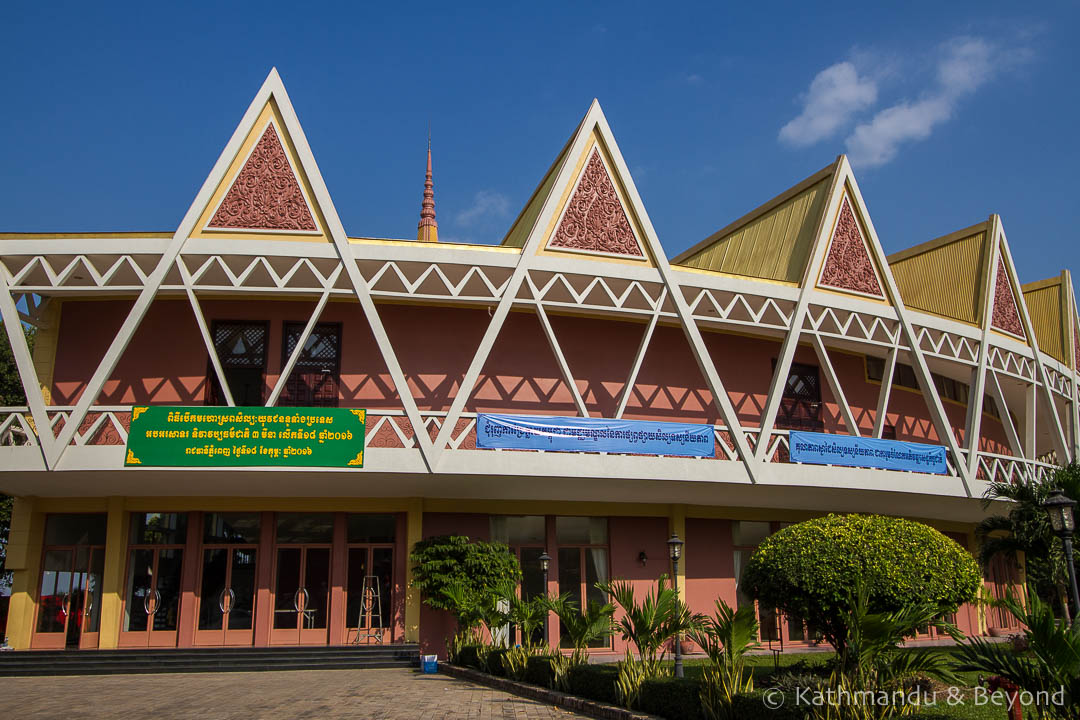

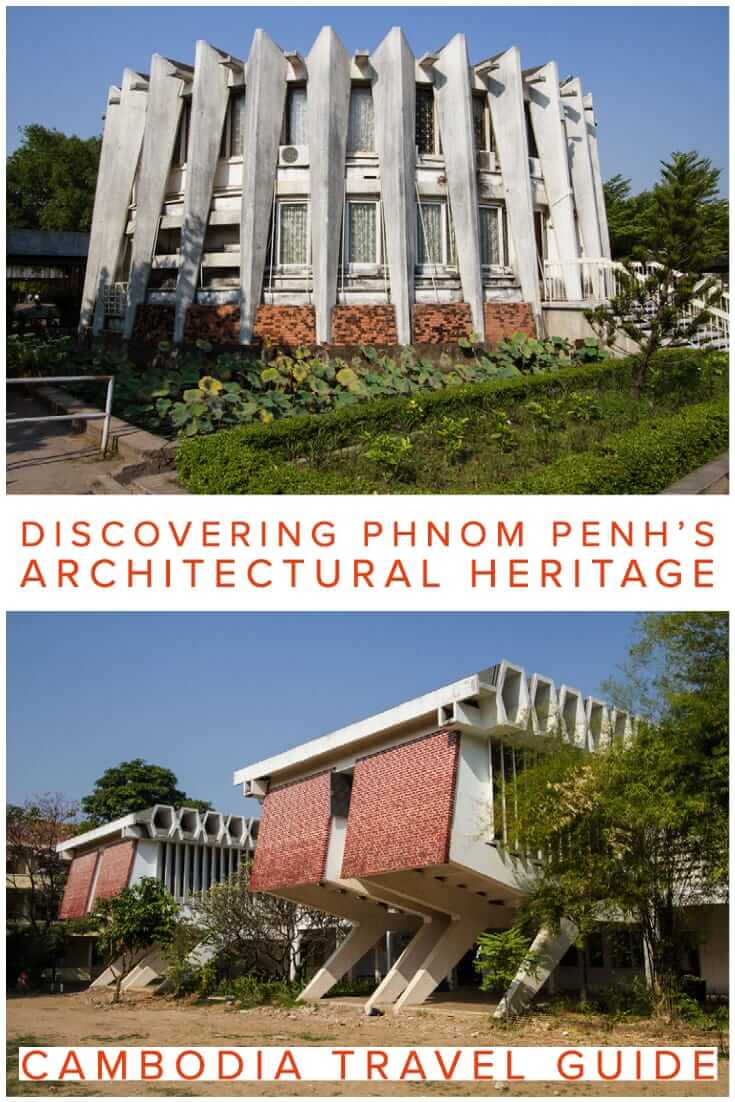

The Institute of Foreign Languages (IFL) is part of the Royal University of Phnom Penh but its distinctive architecture deserves a separate listing in my opinion. Three parts of the faculty are worth seeing from an architectural standpoint: the main building, the library and the lab buildings/classrooms. Originally designed as a Teacher Training College, the complex is the work of Vann Molyvann, who began work on the original blueprints in 1965. The complex was completed in 1971 but the final work was done without the personal supervision of Vann Molyvann who, by now, had relocated himself and his family to Switzerland to avoid the repercussions of the 1970 military coup led by General Lon Nol. Vann Molyvann did not return to Cambodia until 1991. The facility became the Institute of Foreign Languages in 1980 and initially only trained students to be teachers of either Russian or Vietnamese.

Angkor features heavily in Vann Molyvann’s inspiration for the IFL. Elevated walkways, skylights and barays (artificial bodies of water), all of which were common architectural elements of the Khmer Empire, are incorporated into the design of the institute’s main building. There are even stone Nagas (half-human half-serpent deity) guarding the passageway that leads up to its entrance. According to Vann Molyvann, the library is based on a traditional Khmer palm-leaf hat, and the coiled, animal-like design of the lab buildings, which reminds me of the ferocious robot dogs in Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror episode: Metalheads, is mesmerising, to put it mildly. Throw in strong characteristics of brutalist and modernist architecture and it doesn’t take long to realise the whole place is a masterpiece of architectural design and one of my favourite pieces of architecture in Phnom Penh.

Although the IFL is busy with students, nobody seems to mind you wandering around and taking photos of the place. Just keep an eye on the lab buildings in case they spring into action and chase you off the complex!

Institute of Technology of Cambodia

About 800 metres east of the Institute of Foreign Languages, the Institute of Technology of Cambodia is another building worth searching out if you are in the area. This hulk of a structure (not that you’d know it from our shots – it is very difficult to photograph!), was a gift from the Soviet Union and was designed by Soviet architects. It dates from 1964 and after the period of abandonment during the time of the Khmer Rouge, it was renovated and reopened again using French funds.

Apartment Buildings

I have not marked these Phnom Penh architectural gems on the map because there are too many of them but, generally, if you look up as you wander around the streets to the west of the Tonlé Sap River, you will spot many apartment buildings that range from French colonial to modernist in design. Many of them give the appearance of being ramshackle but they are still very much lived in and are an integral part of Phnom Penh’s inner-city housing.

IF YOU ENJOYED OUR GUIDE TO FRENCH COLONIAL AND NEW KHMER ARCHITECTURE IN PHNOM PENH, PLEASE SHARE IT

READ MORE CAMBODIA BLOG POSTS

READ MORE ARCHITECTURE-FOCUSSED POSTS

That was very interesting. I am much more of a fan of Cambodia’s colonial and art deco architecture than the concrete monstrosities of the 1950’s and ’60’s. Brutal indeed. Reminds me of the horrific Le Corbusier buildings in Chandigarh in India. But, de gustibus non disputandum. And I will certainly take your advice and try to do this walking tour if I ever return to Phnom Penh. Thanks.

I’m right into my Brutalism at the moment – been tracking loads of it down in Belarus (where we are at the moment), Minsk in particular is full of the stuff although I was also surprised how grand the city was as well – lots of ornate buildings etc. Apparently it was a show piece for Stalin who had the city rebuilt after WWII. Except a post in the not so distant future.

I’ve been through Chandigarh but never stopped to look around but I know of the Le Corbusier buildings to which you refer. Perhaps I should go there next time I am in India, given my newfound fondness for concrete!!

But do undertake one of the walking tours of Phnom Penh next time you return and remember to look up!

Cine Lux has been undergoing demolition (be it at a painfully slow rate) for the past year. It had been butchered so much over the decades its art deco features had all but disappeared anyway. More recently, the building in front of the Ministry of Industry and Handicrafts has been torn down, although the main building pictured still stands. However it appears a large new building is about to be constructed so the view of the main building may well disappear.

Hi Alex, thank you for the (rather depressing) update. Although, I am not surprised as Phnom Penh is being developed at such a rate and already I’ve had to update this post more than once. Soon I’ll have to re-title the post “Phnom Penh’s Former Distinctive Architecture”! I’ll add a note regarding Cine Lux but could you clarify for me which building in front of the Ministry of Industry and Handicrafts has been torn down – is it the former US Embassy across the road or one of the buildings attached to the ministry? Thanks in advance and I appreciate the feedback.

Mark: Keep doing your good work and spread good news about beautiful old French building in Phnom Penh. Canbodia. We need to talk a lot about this subject or to create an organization to preserve these old colonial buildings from being destroyed by expanding high rise buildings in Phnom Penh.

Thank you for your comment, Jack. A preservation society would be a good idea. To the best of my knowledge there isn’t one but if you ever come across such an organisation, please let me know.