Musings from Mark: some thoughts that seem negative, but are actually positive, rants on Saigon traffic, thoughts for future trips to Vietnam, and eventually to the point… Vietnamese War memorials!

Last February, 2020, as we sat at Ho Chi Minh City (*) airport waiting to board our flight to Bangkok, the overriding thought that was going through my head was that we needed to return to Vietnam as soon as possible and also, that if we were to go ahead with what we were thinking of doing, we had a monumental task ahead of us.

(*) I’m going to call the city Saigon from now on in. I know it is not officially correct, but I don’t know anyone, including Vietnamese, who calls it Ho Chi Minh City. Besides, it’s a faff to write out every time!

Vietnam is not a country that either of us has a clear-cut relationship with. The climate, especially in the central region and upwards from there, can often be appalling, even when it isn’t supposed to be (i.e. when we’ve visited at what is the right time of year, weather-wise). Our last two-week trip before this one, in which we spent the bulk of our time in the central lowlands after Dong Ha, Danang, Hoi An, etc., was literally a complete washout. We had day after day of dampness, persistent rain and low temperatures. We spent most of our time in a sodden state, continually having to wear a clinging, non-breathable poncho when out and about. And by the time we got to Hue, we needed to buy woollen hats and gloves (thank heavens for knock-off Vietnamese North Face), which we also wore in bed to keep warm!

Ponchos are standard kit when bad weather hits northern and central Vietnam

It wasn’t until we reached the tropical climes of Saigon at the tail-end of the trip that we felt comfortable again and had that irritating feeling of knowing that the sweat on your back had just dribbled down the spine and entered below! Not that we were complaining; it was good to feel balmy once more.

Another reason why Vietnam will never be our favourite country in Asia is that, at times, the Vietnamese themselves can be incredibly rude, mean-spirited and dishonest. Of course, this is a sweeping generalisation and I am talking mostly about those who serve the needs of backpackers and other budget-conscious travellers. Certainly not all Vietnamese are like this – far from it, in fact, but, it is a country in which, in certain cities, you continually need to have your wits about you. Hanoi, Hue and Saigon all fall into this category and duel-pricing is a constant irritation. From bus fares to the price of a coconut from a street vendor – it happens all the time and unless you know the cost of something for certain, it’s a continual battle that eventually wears you down.

Then there’s your own safety and that of your processions to consider. Take Saigon for example, where bags, cameras and mobile phones are all fair game for drive-by opportunists on scooters and you have to keep a tight hold on them.

But, what really irks me in Vietnam, and not just in Saigon but in any city of size, is the blatant lack of thought for pedestrians from ALL motorbike riders. I know this is another generalisation but in this instance, it’s a fact – motorbike riders in Vietnam do not give a monkey’s about anyone using their own two legs to get around!

This photo doesn’t especially represent Saigon’s motorbike madness but I wasn’t going to hang around in the middle of the road for too long, just to prove a point!

According to statistics from the country’s Department of Traffic Safety at the Ministry of Transport, there is in the region of 58 million motorbikes in Vietnam, of which 8.5 million of them are in Saigon. Saigon’s municipal population is approximately 9 million. I don’t think I need to do the maths here but, needless to say, that number of motorbikes in any one city is bonkers.

As a pedestrian, it’s a constant battle to get anywhere in Saigon. Locals and tourists alike are all fair game and there is no differentiating between the two. I mention this last point because there are many places we have been where laws of the road are often ignored. Thais, for example, aren’t great believers in stopping for a red light but if they see a monk or a tourist attempting to cross a busy road, they will generally slow down so that you can do so and remain in one piece. In Chiang Mai, we often have Thais come and stand with us if they want to cross the road because they know they stand a better chance of completing the task in hand. We, in turn, search for a monk and hang on to them (not literally!), if the road is looking a bit tricky.

Getting back to Saigon, I’ll admit that the whole “step off the pavement and walk slowly and purposefully, and all the bikes will weave around you” method does work to a certain extent but it’s an unpleasant experience and is only practical when the swarm of bikes all around you are not travelling at any sort of speed. In most cases, it’s a matter of waiting for the tiniest of gaps in the traffic and bolting from one side of the street to the other as if your life depended on it (which it often does!). Kirsty is not a fan of this principle ever since she got knocked off her feet by a car in Saigon, a few years ago.

And even the pavement isn’t the safe haven you’d expect it to be. It’s either used as an additional lane for scooters or as a place to park them on. The continual use of horns as riders sneak up from behind and expect you to get out of their way or the whole having to step off the pavement because there is a line of bikes blocking your path regularly gets me to breaking point when I’m in Vietnam. It was by far and away the worst thing about living and working in Saigon, which we did for three months a couple of years back, and I would often get into an argument with some inconsiderate individual on the route between our apartment and the office (*). By the time our assignment was up, I was desperate to leave Vietnam purely for that reason.

(*) To highlight that not all Vietnamese are as described above, our work colleagues in Saigon were wonderful. We’ve worked in several Southeast Asian countries and, without a doubt, the staff at the office in Saigon were the most efficient as well as being great people to socialise with.

Not everyone gets as wound up by Saigon’s traffic as I do!

So, you might be asking, why are we keen to get back to Vietnam as soon as possible?

Pretty much the only reason why we went to Vietnam in February 2020 was that our three months in Chiang Mai had come to an end and we had no choice but to leave Thailand. If you enter Thailand on a two-month tourist visa, you can only extend it for another month and that’s your lot. Vietnam now allows several nationalities, including British, to stay in Vietnam visa-free for 15 days as long as you have an onward ticket (which they do check). So when a cheap, direct flight from Chiang Mai to Saigon with sociable timings came onto our radar, we decided it would be a decent option to get us out of Thailand. The weather in the south of Vietnam never gets cold so we didn’t have that worry and we reckoned that the Mekong Delta which, at its closest, is only a couple of hours bus ride away, would be way more peaceful and less motorbike-populated than Saigon.

Although we did underestimate the size of some of the cities in the Mekong Delta, like Can Tho and Long Xuyen for example, we mostly got our predictions right and spent a warm and laid back ten days exploring the waterways and settlements of Vietnam’s “Rice Bowl”.

Early morning on the Mekong River in Long Xuyen (Mekong Delta)

And once away from Can Tho, the largest city in the Mekong Delta, we hardly saw any other tourists. As we discovered when we travelled through the country’s also tourist-free Central Highlands a few years back, Vietnam is a very different place away from the tourist hubs of Hoi An, Hue, Sapa and Hanoi etc. We were never knowingly ripped off or (more importantly) felt like we had been and, dare I say, some of the motorbike riders were even considerate to our needs as pedestrians!

It was a good trip and I don’t think it is a coincidence that the two best journeys we have now done in Vietnam have both been in off-the-beaten-track parts of the country. Although, why the Mekong Delta beyond the unimaginative day trip from Saigon is an off-beat destination is a mystery to me, given how easy it is to access.

But that is still not the reason why we need to go back to Vietnam.

One word – monuments …

Before scratching your head and thinking we are a bit odd, let me expand a little. We are not interested in tracking down any old monuments. We are specifically interested in searching for monuments, and memorials, that commemorate both people and events associated with the Vietnam War, or the American War as it is known in Vietnam.

We’ve seen monuments and memorials associated with the Vietnam War elsewhere in the country but never in the abundance that we came across in the Mekong Delta on this last trip.

There was plenty of fierce fighting in the Mekong Delta during the Vietnam War between guerrillas from the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, aka the Viet Cong, and various divisions of the U.S. Army and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnamese). The iconic Swift Boat (as in the waterskiing scene in ‘Apocalypse Now’) was used by the Americans to patrol the delta and intercept seaborne supplies destined for the North Vietnamese Army fighting in the south. Numerous battles and skirmishes took place throughout the entire war, including the Battle of Ben Tre in 1968, where the large-scale destruction led one American officer to state “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it.”

The now medium-sized city of Ben Tre happened to be our first stop in the delta after leaving Saigon. As we were wandering around on the afternoon of our arrival in the uncomfortable and sweltering heat (I know, I know – we are very hard to please!), we spotted the silhouette of, what was unquestionably the backside of a large monument in the distance. After a quick pitstop for a freshly squeezed sugarcane juice (one of our favourite pastimes in Vietnam), we made our way towards the shape in order to take a closer look.

As soon as we clapped eyes on the front of this huge sculpture, we were instantly reminded of the countless number of monuments and memorials we had seen during our travels in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries. Heading back towards our hotel a little later, we spotted another monument in the same style in a small park and yet another one soon after that on the promenade that hugs the city’s length of the Ham Luong River, a branch of the Mekong River.

Examples of Monuments to Glory that we have seen in Central Vietnam (all accompanied by bad weather, of course!). Left: Son My Memorial, which is dedicated to the victims of the infamous My Lai Massacre that took place on 16th March 1968. Centre: Reunification Memorial near the Hien Luong Bridge, which used to be the dividing line between North and South Vietnam during the war – the demilitarized zone, or more commonly, the DMZ. Right: Monument to Mother Suot in Dong Hoi. Nguyen Thi Suot was a 60-year ferry woman who continuously risked her life during the Vietnam War by ferrying Vietnamese soldiers and supplies across the city’s Nhat Le River. She was killed during an American bombing raid in 1968. She later became a heroine of the state and the statue was erected in her honour.

And that was it. From that point on, we decided we would look for these kinds of monuments and memorials in every city and town we visited in the Mekong Delta. As it turned out, because we were travelling around on public transport we only got to see a couple more of these memorials up close but, we did get a glimpse of several more from the window of the bus or minivan we happened to be on when travelling from one place to the next.

By the time we arrived back in Saigon ten days later, we had had a bit of time to do some digging about the Vietnam War memorials in Vietnam. It transpires that information is thin on the ground and there are actually more links on the Internet to memorials in either the United States or Australia (*) than in Vietnam itself. But we did discover information about monuments erected in Saigon and decided to spend our final day in the city searching for some of them.

(*) Australia’s commitment during the Vietnam War was considerable. Fighting alongside the Americans and South Vietnamese, and known for their expertise in jungle warfare, Australian troops and personnel in southern Vietnam numbered in the region of 7,500 at its peak.

It was a successful day from that respect and we used the public bus system (*), which is ridiculously cheap and easy to use, to traverse the city and track down what we had earmarked.

(*) As an aside, there is a perverse enjoyment to riding the bus in Saigon. Obviously, buses are bigger than scooters and it gives me great pleasure to watch the latter be forced to scurry out of the way as the bus you are on, which nine times out of ten is in the hands of a maniacal driver with psychopathic tendencies, hurtles along at breakneck speed with the horn going ten to the dozen!

The success in Saigon and the certainty that we knew from passing glimpses that there were many more monuments in the Mekong Delta got us thinking.

As with most of the inspiration for our future travel plans, they come to us when we are sitting in a bar and that evening, hemmed in on tiny stools at a roadside joint on Bui Vien Street (Saigon’s backpacker area), we came up with the idea that it would be interesting to undertake a country-wide mission to find and document as many of these monuments as possible.

The last time we went on a trip that was predominantly dedicated to finding monuments was in Bulgaria in the summer of 2019. We were specifically searching for monuments erected during the country’s communist period and the journey turned out to be a great success in that we saw almost double the amount of monuments and memorials we had anticipated. What helped on that particular trip was that we had our own transport in the form of a small car we hired in Varna on the Black Sea Coast. Driving in Bulgaria had its moments but we had no serious issues and, overall, the experience was fine and dandy.

But, driving a car in Vietnam is a completely different ball game!

I don’t even know if you can hire a car in Vietnam? I’m sure you can but, in my opinion, you would have to be slightly insane to want to do so. Chaos reigns on the roads even in the smallest of towns in Vietnam – swarms of motorbikes and other forms of transport all heading in any direction that pleases and the continuous feeling that you are surrounded by an army of ants – blow that for a game of soldiers!

Even after several more beers on Bui Vien Street, we concluded that driving ourselves in Vietnam was a very bad idea and so we explored other avenues.

Given how many monuments we missed in the Mekong Delta, relying on public transport wasn’t going to be a practical option for this kind of trip, and hiring transport with a driver would probably end up being quite costly. Also, we would want the flexibility to stop as and when. The reason why we saw more monuments than expected in Bulgaria was exactly for this reason and if you don’t have total control of your means of transport, it’s not easy to have this flexibility.

After a few more beers and a quick mindless chat with a couple of young, puppy-like travellers on the next table, we concluded that the only option was to adopt the old adage of, “If you can’t beat them, join them.”

Hence, as and when we decide to do this monumental (get it!) journey, we will do so on a motorbike. It’s the only logical means of undertaking this trip. Plus, it will give us complete flexibility and will not be too expensive.

Motorbiking has been a popular means of discovering Vietnam (and other parts of Indochina) for travellers for some time now. If you don’t want the hassle of buying and re-selling a bike, there are companies that provide rental, including one-way drop-off, as well as a backup service should you encounter any mechanical issues along the way. It is also possible to join small groups or ride pillion if you don’t fancy riding yourself. You can even have the bike fitted with an extended rack that is purposely designed for rucksacks. There are plenty of options for seeing Vietnam on a motorbike these days and so long as you don’t think too much about the other 58 million bikes and scooters on the road, it’s a good way to see the country!

We have ridden scooters before but only under supervision! We’ve gone on a number of excursions with the excellent Vespa Adventures in both Vietnam and Cambodia. Contrary to what this photo might suggest, you are accompanied by experienced riders and a guide and we would highly recommend joining one. We’ve written a post about the one we did in Phnom Penh, but my personal favourite was the one we went on in Saigon, where you ride pillion and zip through the streets of Cholon and other busy districts in the city.

For us, our dabble in the world of motorbiking in Vietnam isn’t going to happen anytime soon. We have other plans in place for the (not so) foreseeable future and, of course, there’s that little thing called COVID-19 putting the kybosh on everything at the moment. We try and return to Chiang Mai in Thailand at least every other year and for various reasons, which I won’t go into now, we struggle to find other destinations to combine our Chiang Mai time with. But, we like socialist realism, the sanctioned art form of the Soviet Union and the inspiration for many of the glory memorials in Vietnam, plus, we enjoy getting off the beaten track and are always up for a good road trip, so another visit to Vietnam will fill the ‘other destination’ void perfectly when the time comes.

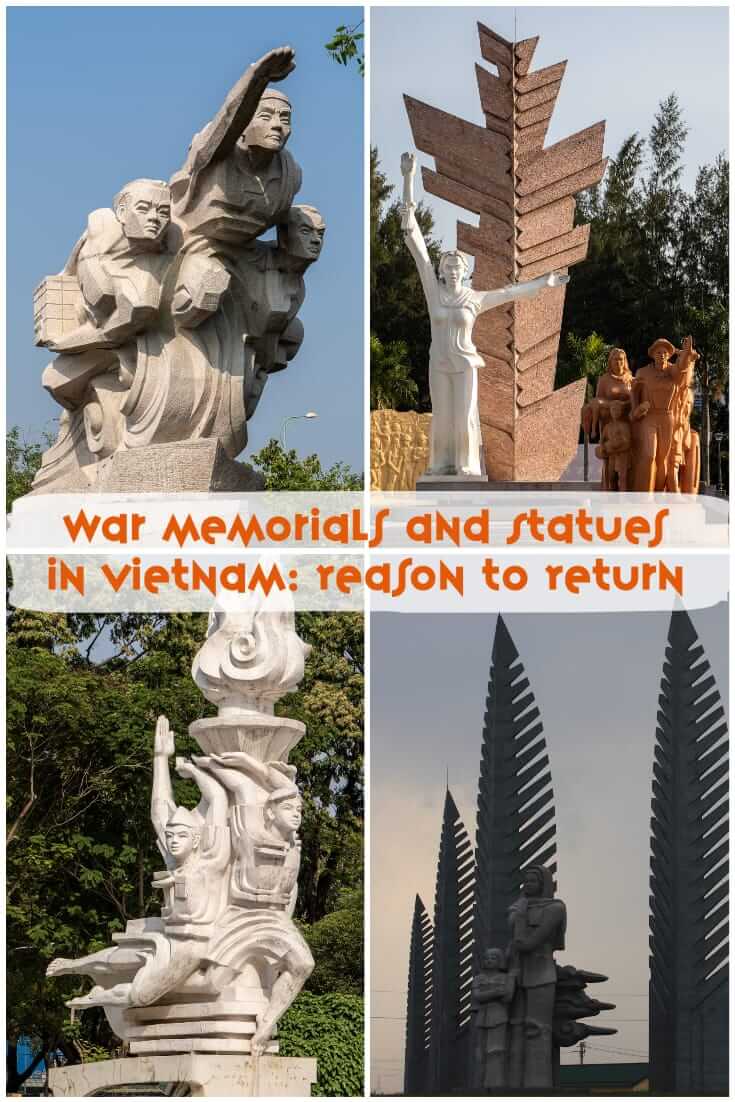

To round off this post, and as a taster of what’s (eventually) to come, here are few examples of the monuments and memorials we discovered in Saigon and the Mekong Delta.

Incidentally, if this sort of thing interests you but you don’t have the inclination or the time to undertake a journey of the magnitude described above, then head to the Fine Arts Museum in Saigon. There are several monuments in the style of socialist realism in the courtyard and an interesting display of combat art inside the building itself.

Monument to the Workers Struggle, Saigon

Here is an example of the mayhem caused by motorbikes in Saigon. We found it impossible to cross to the roundabout on which this monument was located and had to be content with photographing it from a distance and with a big lens.

Monument to the Workers Struggle, Saigon

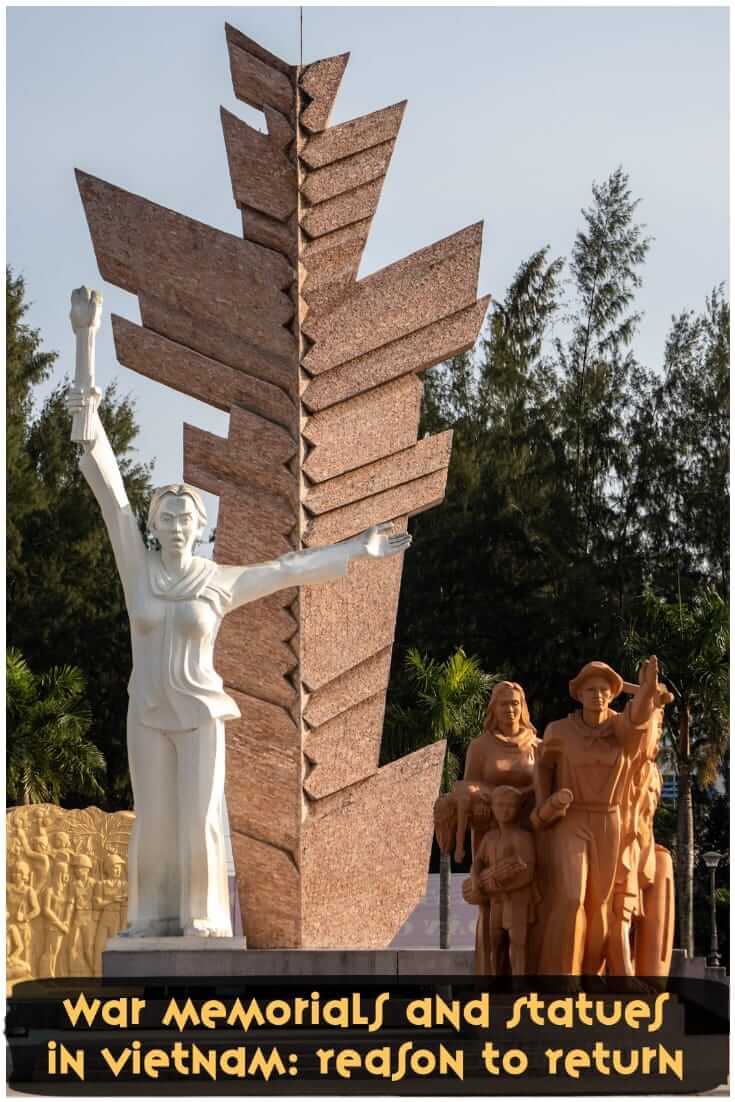

Dong Khoi Monument, Ben Tre

We didn’t realise the significance of this monument until later on. Dong Khoi was a revolutionary movement that urged the (predominantly) peasant society in the south of Vietnam to rebel against the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) and the United States. Instigated in late 1959 by members of the Viet Minh, the movement spread rapidly and by 1960, many rural areas in the south of the country were under the control of the communists which, in turn, led to the founding of the Viet Cong. The insurgency in southern Vietnam is often viewed as the beginning of the Vietnam War.

Dong Khoi Monument, Ben Tre

Monument to Le Van Tam, Saigon

Le Van Tam was a teenage Vietnamese revolutionary during the First Indochina War (1946-1954) against the French (*). It is believed that he martyred himself destroying a French arsenal in January 1946. After the Vietnam War ended in 1975, he was elevated to the status of national hero and parks, schools and roads etc. were named after him. His story was also added to school textbooks. There is a question mark, however, as to whether Le Van Tam was a real person or not. Some sources say that he was, while others state that he was a fictional character created as propaganda to inspire the people. The monument is located in a park of the same name, which used to be Saigon’s European Cemetery, a historic French colonial-era graveyard. It was abolished by the communist government in the early 1980s because it was viewed as a reminder of Vietnam’s colonial past.

(*) The Vietnam War that I mainly speak of in this post is sometimes referred to as the Second Indochina War.

Monument to Le Van Tam, Saigon

Monument to the People of Victory, Tra Vinh

Also called the North Vietnam Victory Memorial, this huge monument on the outskirts of Tra Vinh is a slap-in-the-face reminder as to which side won the conflict. It’s an impressive sculpture, and the detailed mosaics either side of the plinth wouldn’t look out of place in one of the republics that once formed the Soviet Union. Unlike monuments of this kind in the former USSR, however, this one is extremely well attended. In fact, the same statement can be made about all the monuments to glory that we have seen to date in Vietnam. This one has recently undergone restoration work and, what’s more, we nearly ended up soaked because overzealous gardeners didn’t spot us while watering the shrubs with a water cannon!

Monument to the People of Victory, Tra Vinh

Monument to Tran Van On, Ben Tre

Tran Van On was a student activist who opposed French rule in Vietnam. He had joined a patriotic student movement in the late 1940s and spent much of his time producing propaganda and mobilising other students to rise up against French rule. During a 6,000-strong student rally in Saigon on 9th January 1950, Tran Van On was shot dead by police tasked with breaking up the gathering. This sparked another wave of rallying and at his funeral, three days later, in the region of half a million students and other protesters took to the streets of Saigon, with many coming from other parts of the country to take part. The following month, 9th January was declared Student Day in Vietnam and after the war, he was officially recognised as a martyr and eventually awarded the prestigious title Hero of the People’s Armed Force.

Tran Van On was born and raised near Ben Tre, before moving to Saigon to continue his studies. Hence, I’m assuming this is the reason why there is a monument dedicated to him in the city.

Monument to Tran Van On, Ben Tre

War Memorial, Sa Dec

There were lots of detailed scenes on this memorial in the sleepy riverside town of Sa Dec. The information plaque attached to it is in Vietnamese but it does have the year 1946 included on it. As the First Indochina War began in 1946, I’m assuming that the memorial commemorates either the war itself or an event that happened during it in, or nearby, Sa Dec. During the Vietnam War, Sa Dec was a U.S. Navy Swift Boat base. Today, it is one of the most delightful towns in the Mekong Delta and a lovely place to hang out for a day or two.

War Memorial, Sa Dec

Monument to the People of District 5, Saigon

There are two sides to this monument, with women on one side and men on the other. The western half of District 5 is part of Cholon, the city’s Chinatown, which is considered to be the largest Chinatown in the world. During the Vietnam War, Cholon was the go-to place for black market goods, especially American Army-issue kit, etc.

Monument to the People of District 5, Saigon

Victory Monument, Ben Tre

This relatively recent monument (2008) commemorates the destruction of several U.S. Navy boats by Viet Cong forces. The plaque attached to the monument is self-explanatory and more or less translates as follows:

With honourable achievements, the riverine special elite force of Ben Tre was awarded the title Hero of the People’s Armed Forces and the golden motto “ride the waves of Ham Luong River, sink the fleets of U.S. Navy.”

Victory Monument, Ben Tre

READ MORE BLOG POSTS FEATURING VIETNAM

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS RATHER OBSCURE FEATURING MARK’S RAMBLES ABOUT OUR TRAVELS TO VIETNAM PLUS THE VIETNAMESE MONUMENTS INCLUDED… PLEASE SHARE IT!

Missed this last summer, but loved reading it now, especially your rant (your word, not mine, but entirely justifiable) about traffic in Saigon. I haven’t been back to Vietnam since I was there for a month in 1992. Then the streets of Saigon were a sea of cyclos. Very few cars or even motorcycles. Still very annoying and intimidating for pedestrians, but no doubt better than now. And I, too, loved the Mekong Delta, spending five or so days there with stays in My Tho, Can Tho and Chau Doc. Now I’m sorry I missed Sa Dec. I don’t remember any memorials in Soviet Realism style in 1992. Only memorials I remember we’re composed of old war equipment: tanks, planes, artillery and the like. Did Soviet Realism style memorials blossom in Vietnam only in the decades after the Soviet Union itself collapsed?

We lived in Saigon for 3 months a few years back and the traffic drove me insane!. Your question re the monuments is a good one and I’m not 100% of the answer but I suspect the answer is yes. My theory is that pre the early 1990s, the country was too busy putting itself back together after the war to concern itself with war memorials but once things had normalised, these memorials began to sprout up to commemorate significant events that took place during the conflict. I only have confirmed dates for a few of the ones we have seen and they are all post-1995, hence that is probably the reason why you didn’t remember seeing any during your trip. I was also there in 1992 and also don’t recall seeing any.

I’ve heard how crazy roads are in Vietnam but I didn’t know the extent of it until I read this post! To think that even pavements are not safe either ! I love your honesty and how you wrote about things that most bloggers don’t.